The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is scheduled to launch on 25 December. To mark the event, Physics World is publishing a series of blog posts on the telescope’s technological innovations and scientific missions. This post is the fifth in the series. Read the first here.

Given the hype surrounding its scheduled launch on 25 December, you’d be forgiven for thinking the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is the only major astronomy facility due to come online in the 2020s. In fact, it is one of three: the Vera C Rubin Observatory will see first light in Chile in 2022, while the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope is currently scheduled to launch in 2027. Both facilities will be leaders in all-sky survey work, where the emphasis is on observing as many objects as possible across a wide swathe of sky. Such surveys are vital for collecting data on large numbers of objects; among other projects, they provide the statistics behind efforts to measure the strength of dark energy.

The current leader in this field is the Nicholas U Mayall four-metre telescope at Kitt Peak National Observatory, where the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) can make 5000 spectroscopic observations at once. That figure is well beyond the JWST’s capabilities, but the new space telescope will nevertheless do its fair share of astronomical surveying thanks to its Near Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec). This instrument can collect spectroscopic data on 100 objects at once, granting the JWST a capability that no other space telescope has ever had and giving astronomers a fresh eye for their surveys.

To make the JWST fit for survey work, its designers had to look beyond the technology already in use at DESI. In the past, making simultaneous observations was a laborious process, one that involved manually fixing optical fibres at holes punched in an aluminium plate. DESI avoids this thanks to robotic actuators that position the fibres anywhere across the instrument’s field of view and can be moved every 20 minutes, allowing a huge number of observations to take place in a single night. Unfortunately, this solution was deemed unworkable for a space-based observatory. “We looked at DESI’s robotic fibres when we were choosing what to do on [the JWST], and we were completely in awe of the robotic capabilities that it would take to do that in space,” senior project scientist John Mather tells Physics World.

With robotic actuators unable to operate reliably at the JWST’s cryogenic temperatures, and no human technicians available to change the position of its optical fibres manually, Mather and his colleagues needed a different solution. In fact, they needed a solution that didn’t involve optical fibres at all, since “there are no optical fibres that would cover the whole range of wavelengths that we want to cover”, Mather says.

The ten-billion-dollar gamble: Keeping the JWST cool

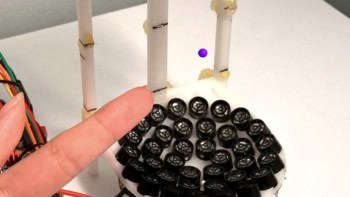

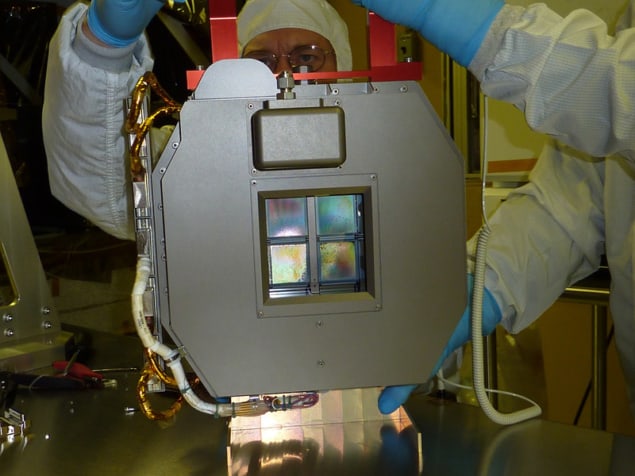

The NIRSpec team’s answer is an ingenious one. The instrument’s focal plane is divided into four quadrants, each about the size of a postage stamp and filled with 62,000 microshutters. Each microshutter measures just 100 × 200 μm and is made from silicon nitride, which has a high tensile strength and is tough enough for the shutters to open and close many times without fatiguing. During each observation, the shutters that need to open will receive an electrical signal from a magnetic arm that sweeps over the quadrants. This system will allow the telescope to study the spectra of thousands of the most distant galaxies during its mission, learning about their chemistry, star-formation rates, redshift and more.

Next: How the JWST will see deep into the universe’s past

- This article was amended on 22 December 2021 to reflect delays to the JWST’s launch date.