Pairs of nonidentical particles trapped in adjacent nodes of a standing wave can harvest energy from the wave and spontaneously begin to oscillate, researchers in the US have shown. What is more, these interactions appear to violate Newton’s third law. The researchers believe their system, which is a simple example of a classical time crystal, could offer an easy way to measure mass with high precision. It might also, they hope, provide insights into emergent periodic phenomena in nature.

Acoustic tweezers use sound waves to create a potential-energy well that can hold an object in place – they are the acoustic analogue of optical tweezers. In the case of a single trapped object, this can be treated as a dissipationless process, in which the particle neither gains nor loses energy from the trapping wave.

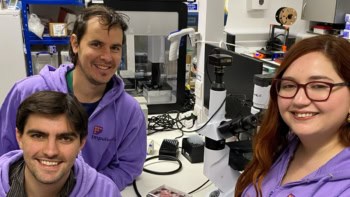

In the new work, David Grier of New York University, together with graduate student Mia Morrell and undergraduate Leela Elliott, created an ultrasound standing wave in a cavity and levitated two objects (beads) in adjacent nodes.

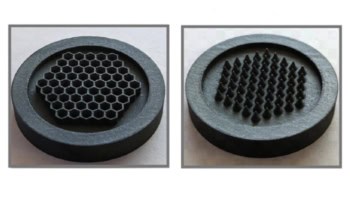

“Ordinarily, you’d say ‘OK, they’re just going to sit there quietly and do nothing’,” says Grier; “And if the particles are identical, that’s exactly what’s going to happen.”

Breaking the law

If the two particles differ in size, material or any other property that affects acoustic scattering, they can spontaneously begin to oscillate. Even more surprisingly, this motion appears unconstrained by the requirement that momentum be conserved – Newton’s third law.

“Who ordered that?”, muses Grier.

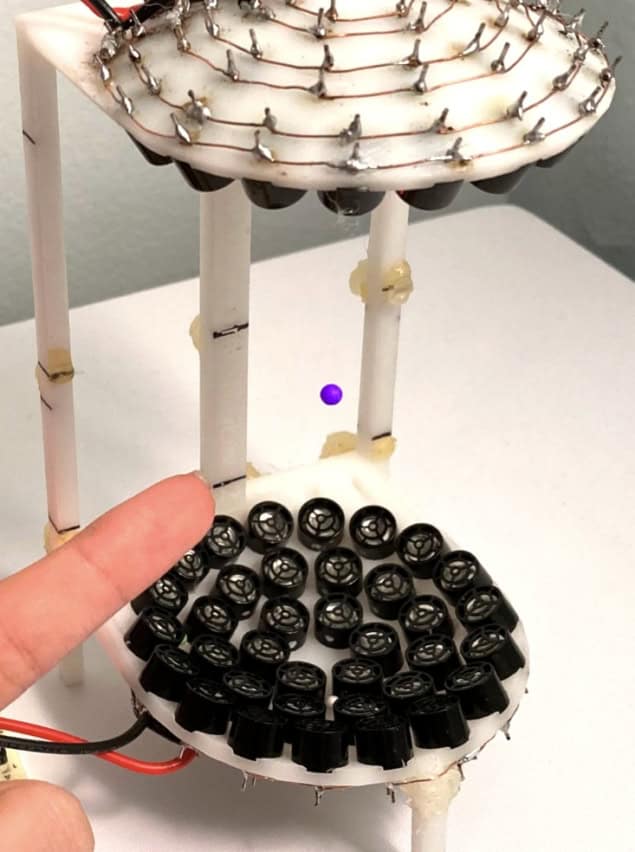

The periodic oscillation, which has a frequency parametrized only by the properties of the particles and independent of the trapping frequency, forms a very simple type of emergent active matter called a time crystal.

The trio analysed the behaviour of adjacent particles trapped in this manner using the laws of classical mechanics, and discovered an important subtlety had been missed. When identical particles are trapped in nearby nodes, they interact by scattering waves, but the interactions are equal and opposite and therefore cancel.

“The part that had never been worked out before in detail is what happens when you have two particles with different properties interacting with each other,” says Grier. “And if you put in the hard work, which Mia and Leela did, what you find is that to the first approximation there’s nothing out of the ordinary.” At the second order, however, the expansion contains a nonreciprocal term. “That opens up all sorts of opportunities for new physics, and one of the most striking and surprising outcomes is this time crystal.”

Stealing energy

This nonreciprocity arises because, if one particle is more strongly affected by the mutual scattering than the other, it can be pushed farther away from the node of the standing wave and pick up potential energy, which can then be transferred through scattering to the other particle. “The unbalanced forces give the levitated particles the opportunity to steal some energy from the wave that they ordinarily wouldn’t have had access to,” explains Grier. The wave also carries away the missing momentum, resolving the apparent violation of Newton’s third law.

If it were acting in isolation, this energy input would make the oscillations unstable and throw the particles out of the nodes. However, energy is removed by viscosity: “If everything is absolutely right, the rate at which the particles consume energy exactly balances the rate at which they lose energy to viscous drag, and if you get that perfect, delicious balance, then the particles can jiggle in place forever, taking the fuel from the wave and dumping it back into the system as heat.” This can be stable indefinitely.

Space–time crystal emerges in a liquid crystal

The researchers have filed a patent application for the use of the system to measure particle masses with microgram-scale precision from the oscillation frequency. Beyond this, they hope the phenomenon will offer insights into emergent periodic phenomena across timescales in nature: “Your neurons fire at kilohertz, but the pacemaker in your heart hopefully goes about once per second,” explains Grier.

The research is described in Physical Review Letters.

“When I read this I got somehow surprised,” says Glauber Silva of The Federal University of Alagoas in Brazil; “The whole thing of how to get energy from the surrounding fields and produce motion of the coupled particles is something that the theoretical framework of this field didn’t spot before.”

“I’ve done some work in the past, both in simulations and in optical systems that are analogous to this, where similar things happen, but not nearly as well controlled as in this particular experiment,” says Dustin Kleckner of University of California, Merced. He believes this will open up a variety of further questions: “What happens if you have more than two? What are the rules? How do we understand what’s going on and can we do more interesting things with it?” he says.