Tushna Commissariat reviews Through Two Doors at Once: the Elegant Experiment that Captures the Enigma of Quantum Reality by Anil Ananthaswamy

“The experiment I am about to relate…may be repeated with great ease, wherever the sun shines.” That was how polymath Thomas Young described his newly devised experiment that revealed the true nature of light, to the members of the Royal Society in November 1803. Young was referring to the very first iteration of what we now know as the “double-slit experiment”, which forms the backbone of quantum mechanics and reveals to us the truly baffling way in which light behaves. In Through Two Doors at Once: the Elegant Experiment that Captures the Enigma of Quantum Reality, author Anil Ananthaswamy dives into the 200-year history, science and legacy of this beautiful and inscrutable experiment.

A journalist by trade, Ananthaswamy has written for a number of publications, including New Scientist, Nature, the Wall Street Journal and, indeed, Physics World; but he has also penned a few popular-science books over the years. His first, The Edge of Physics – a travelogue-style book, covering cutting-edge experiments in cosmology located in some of the most extreme locations on the planet – did particularly well, and even won our 2010 Book of the Year award. His second book The Man Who Wasn’t There, which dealt with the complex and difficult subject of mental disorders and the neuroscience behind them, was equally well received. With this latest book, Ananthaswamy has once more picked a labyrinth of a subject, as he attempts to nail down what we do and don’t know about the nature of light.

To describe the double-slit experiment as an enigma is an understatement

To describe the double-slit experiment as an enigma is an understatement. Despite being around for over two centuries, the experiment has equally delighted and frustrated the best and brightest minds in physics, from Albert Einstein, Erwin Schrödinger and Werner Heisenberg to some of today’s top physicists, including Anton Zeilinger, Alain Aspect and Roger Penrose. Its results and conclusions are still a matter of debate. But despite the uncertainty that surrounds the experiment, it is one that is indeed as simple to perform as Young suggested, and so is taught to physics undergraduates the world over. When I carried out the experiment as an undergrad, it was a sweltering hot summer day in India, and despite the overabundance of sunlight, we used a sodium vapour lamp and had to work behind thick black curtains. I was so focused on setting up my grating to get a perfect diffraction pattern (the aim of the experiment was to calculate the half angular width of the central maximum) that I completely missed the truly spectacular implications of the experiment itself.

It was only later, when we studied the theory behind the experiment in depth, that its mind-boggling aspects were revealed to me. Although the smallest unit of light – a quantum – is a particle, it can also behave like a wave. The very act of us observing (or not observing) quantum particles seems to change the outcome of the experiment. The double-slit experiment, done with a single quantum particle, still produces an interference pattern. And for whatever reason, there seems to be some boundary between the quantum and classical worlds – after all, the Schrödinger’s cat experiment does not work with actual cats.

It’s no surprise then that Ananthaswamy felt compelled to pen an entire book on this one experiment, albeit going into its many forms and versions. The book does a very good job at describing how the experiment has grown and developed since Young’s first rudimentary set-up (there wasn’t even one slit, let alone two), which involved a pinhole in the shutter of his window and a piece of card he held up to split the incoming ray of sunlight.

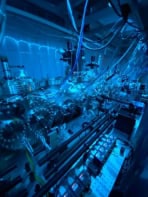

Today, we have diffraction gratings that are much slimmer than a strand of hair, laser beams of all strengths and advanced light-detectors to pick up the patterns. I recall a team of scientists fabricating a grating from graphene, while another used the silica-based exoskeleton of a diatom (unicellular marine algae) to split up light. Not only that, researchers have discovered that it works with not just light but also any number of quantum particles, including electrons, large molecules and, in one rather unbelievable instance, a bacterium.

An enjoyable and useful aspect of Through Two Doors at Once is the fact that Ananthaswamy has not only covered the historical aspects of the experiment (not to mention other related facets of quantum theory, its interpretations and more), but also devoted nearly half the book to describing the much more recent studies featuring the double slit. These include the famous entanglement experiments carried out by Zeilinger and colleagues, where photons were sent over a distance of 144 km, with the experiment set up over two mountain-tops in the Canary Islands. I particularly enjoyed the chapter where he meets up with Penrose to talk about the latter’s ideas on the quantum–classical boundary and some of the issues around the measurement problem – that the act of measurement is necessary for a wavefunction to collapse. Penrose’s ideas and solutions, which involve the curvature of space–time and certain inherent properties of gravity (you’ll have to read the book to learn more), are rather radical, but no less perplexing that the reality of quantum mechanics itself.

Ananthaswamy’s writing is nearly always lucid, although lay readers may find certain parts – such as the chapter on the delayed-choice quantum eraser experiment – hard going. The book is not chronological in its description of the science, but I can see why the author has chosen to divide it by topic instead. Through Two Doors at Once is a fascinating read and a must for anyone who would like to find out the latest experimental advances made in this most fundamental of quantum experiments. Don’t expect a resolution though – we’re still far from cracking the many mysteries of the double-slit experiment, and the book’s last sentence enticingly reads “The case remains unsolved.”

- 2018 Penguin Random House, 304pp, £15.99hb