VolkVac Instruments makes lightweight UHV suitcases that are used to transport delicate samples long distances while under vacuum. It has teamed up with bi-metal and aluminium vacuum experts at Atlas Technologies to develop the next generation of its products.

UHV suitcases address an important challenge facing people who use ultrahigh vacuum (UHV) systems: it can be extremely difficult to move samples from one UHV system to another without the risk of contamination. While some UHV experiments are self contained, it is often the case that research benefits from using cutting-edge analytical techniques that are only available at large facilities such as synchrotrons, free-electron lasers and neutron sources.

Normally, fabricating a UHV sample in one place and studying it in another involves breaking the vacuum and then removing and transporting the sample. This is unsatisfactory for two reasons. First, no matter how clean a handling system is, exposing a sample to air will change or even destroy its material properties – often irrevocably. The second problem is that an opened UHV chamber must be baked out before it can be used again – and a bakeout can take several days out of a busy research schedule.

These problems can be avoided by connecting a portable UHV system (called a UHV suitcase) to the main vacuum chamber and then transferring the sample between the two. This UHV suitcase can then be used to move the sample across a university campus – or indeed, halfway around the world – where it can be transferred to another UHV system.

Ultralight aluminium UHV suitcases

While commercial designs have improved significantly over the past two decades, today’s UHV suitcases can still be heavy, unwieldy and expensive. To address these shortcomings, US-based VolkVac Instruments has developed the ULSC ultralight aluminium suitcase, which weighs less than 10 kg, and an even lighter version – the ULSC-R – which weighs in at less than 7 kg.

Key to the success of VolkVac’s UHV suitcases is the use of lightweight aluminium to create the portable vacuum chamber. The metal is used instead of stainless steel, a more conventional material for UHV chambers. As well as being lighter, aluminium is also much easier to machine. This means that VolkVac’s UHV suitcases can be efficiently machined from a single piece of aluminium. The lightweight material is also non-magnetic. This is an important feature for VolkVac because it means the suitcases can be used to transport samples with delicate magnetic properties.

Based in Escondido, California, VolkVac was founded in 2020 by the PhD physicist Igor Pinchuk. He says that the idea of a UHV suitcase is not new – pointing out that researchers have been creating their own bespoke solutions for decades. The earliest were simply standard vacuum chambers that were disconnected from one UHV system and then quickly wheeled to another – without being pumped.

This has changed in recent years with the arrival of new materials, vacuum pumps, pump controllers and batteries. It is now possible to create a lightweight, portable UHV chamber with a combination of passive and battery-powered pumps. Pinchuk explains that having an integrated pump is crucial because it is the only way to maintain a true UHV environment during transport.

Including pumps, controllers and batteries means that the material used to create the chamber of a UHV suitcase must be as light as possible to keep the overall weight to a minimum.

Aluminium is the ideal material

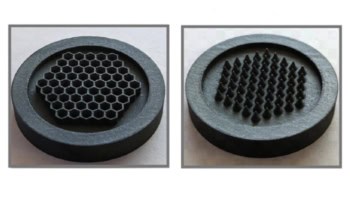

While aluminium is the ideal material for making UHV suitcases, it has one shortcoming – it is a relatively soft metal. Access to UHV chambers is provided by conflat flanges which have sharp circular edges that are driven into a copper-ring gasket to create an exceptionally airtight seal. The problem is that aluminium is too soft to provide durable long-lasting sharp knife edges on flanges.

This is why VolkVac has looked to Atlas Technologies for its expertise in bi-metal fabrication. Atlas fabricate aluminium flanges with titanium or stainless steel knife-edges. Because VolkVac requires non-magnetic materials for its UHV suitcases, Atlas developed titanium–aluminium flanges for the company.

Atlas Technologies’ Jimmy Stewart coordinates the company’s collaboration with VolkVac. He says that the first components for Pinchuk’s newest UHV suitcase, a custom iteration of VolkVac’s ULSC, have already been machined. He explains that VolkVac continues to work very closely with Atlas’s lead machinist and lead engineer to bring Pinchuk’s vision to life in aluminium and titanium.

Close relationship between Atlas and VolkVac

Stewart explains that this close relationship is necessary because bi-metal materials have very special requirements when it comes to things like welding and stress relief.

Stewart adds that Atlas often works like this with its customers to produce equipment that is used across a wide range of sectors including semiconductor fabrication, quantum computing and space exploration.

Because of the historical use of stainless steel in UHV systems, Stewart says that some customers have not yet used bi-metal components. “They may have heard about the benefits of bi-metal,” says Stewart, “but they don’t have the expertise. And that’s why they come to us – for our 30 years of experience and in-depth knowledge of bi-metal and aluminium vacuum.” He adds, “Atlas invented the market and pioneered the use of bi-metal components.”

Pinchuk agrees, saying that he knows stainless steel UHV technology forwards and backwards, but now he is benefitting from Atlas’s expertise in aluminium and bi-metal technology for his product development.

Three-plus decades of bi-metal expertise

Atlas Technologies was founded in 1993 by father and son Richard and Jed Bothell. Based in Port Townsend, Washington, the company specializes in creating aluminium vacuum chambers with bi-metal flanges. Atlas also designs and manufactures standard and custom bi-metal fittings for use outside of UHV applications.

Binding metals to aluminium to create vacuum components is a tricky business. The weld must be UHV compatible in terms of maintaining low pressure and not being prone to structural failure during the heating and cooling cycles of bakeout – or when components are cooled to cryogenic temperatures.

Jed Bothell points out that Japanese companies had pioneered the development of aluminium vacuum chambers but had struggled to create good-quality flanges. In the early 1990s, he was selling explosion-welded couplings and had no vacuum experience. His father, however, was familiar with the vacuum industry and realized that there was a business opportunity in creating bi-metal components for vacuum systems and other uses.

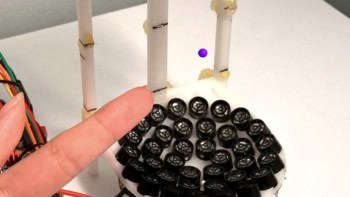

Explosion welding is a solid-phase technique whereby two plates of different metals are placed on top of each other. The top plate is then covered with an explosive material that is detonated starting at an edge. The force of the explosion pushes the plates together, plasticizing both metals and causing them to stick together. The interface between the two materials is wavy, which increases the bonded surface area and strengthens the bond.

Strong bi-metal bond

What is more, the air at the interface between the two metals is ionized, creating a plasma that travels along the interface ahead of the weld, driving out impurities before the weld is made – which further strengthens the bond. The resulting bi-metal material is then machined to create UHV flanges and other components.

As well as bonding aluminium to stainless steel, explosive welding can be used to create bi-metal structures of titanium and aluminium – avoiding the poor UHV properties of stainless steel.

“Stainless steel is bad material for vacuum in a lot of ways,” Bothell explains, He describes the hydrogen outgassing problem as “serious headwind” against using stainless steel for UHV (see box “UHV and XHV: science and industry benefit from bi-metal fabrication”). That is why Atlas developed bi-metal technologies that allow aluminium to be used in UHV components – and Bothell adds that it also shows promise for extreme high vacuum (XHV).

UHV and XHV: science and industry benefit from bi-metal fabrication

Modern experiments in condensed matter physics, materials science and chemistry often involve the fabrication and characterization of atomic-scale structures on surfaces. Usually, such experiments cannot be done at atmospheric pressure because samples would be immediately contaminated by gas molecules. Instead, these studies must be done in either UHV or XHV chambers – which both operate in the near absence of air. UHV and XHV also have important industrial applications including the fabrication of semiconductor chips.

UHV systems operate at pressures in the range 10−6–10−9 pa and XHV systems work at pressures of 10−10 pa and lower. In comparison, atmospheric pressure is about 105 pa.

At UHV pressures, it takes several days for a single layer (monolayer) of contaminant gases to build up on a surface – whereas surfaces in XHV will remain pristine for hundreds of days. These low pressures also allow beams of charged particles such as electrons, protons and ions to travel unperturbed by collisions with gas molecules.

Crucial roles in science and industry

As a result UHV and XHV vacuum technologies play crucial roles in particle accelerators and support powerful analytical techniques including angle resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES), Auger electron spectroscopy (AES), secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS) and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS).

UHV and XHV also allow exciting new materials to be created by depositing atoms or molecules on surfaces with atomic-layer precision – using techniques such as molecular beam epitaxy. This is very important in the fabrication of advanced semiconductors and other materials.

Traditionally, UHV components are made from stainless steel, whereas XHV systems are increasingly made from titanium. The latter is expensive and a much more difficult material to machine than stainless steel. As a result, titanium tends to be reserved for more specialized applications such as the X-ray lithography of semiconductor devices, particle-physics experiments and cryogenic systems. Unlike stainless steel, titanium is non-magnetic so it is also used in experiments that must be done in very low magnetic fields.

An important shortcoming of stainless steel is that the process used to create the material leaves it full of hydrogen, which finds its way into UHV chambers via a process called outgassing. Much of this hydrogen can be driven out by heating the stainless steel while the chamber is being pumped down to UHV pressures – a process called bakeout. But some hydrogen will be reabsorbed when the chamber is opened to the atmosphere, and therefore time-consuming bakeouts must be repeated every time a chamber is open.

Less hydrogen and hydrocarbon contamination

Aluminium contains about ten million times less hydrogen than stainless steel and it absorbs much less gas from the atmosphere when a UHV chamber is opened. And because aluminium contains a low amount of carbon, it results in less hydrocarbon-based contamination of the vacuum

Good thermal properties are crucial for UHV materials and aluminium conducts heat ten times better than stainless steel. This means that the chamber can be heated and cooled down much more quickly – without the undesirable hot and cold spots that affect stainless steel. As a bonus, aluminium bakeout can be done at 150 °C, whereas stainless steel must be heated to 250 °C. Furthermore, aluminium vacuum chambers retain most of the gains from previous bakeouts making them ideal for industrial applications where process up-time is highly valued.

Magnetic fields can have detrimental effects on experiments done at UHV, so aluminium’s slow magnetic permeability is ideal. The material also has low residual radioactivity and greater resistance to corrosion than stainless steel – making it favourable for use in high neutron-flux environments. Aluminium is also better at dampening vibrations than stainless steel – making delicate measurements possible.

When it comes to designing and fabricating components, aluminium is much easier to machine than stainless steel. This means that a greater variety of component shapes can be quickly made at a lower cost.

Aluminium is not as strong as stainless steel, which means more material is required. But thanks to its low density, about one third that of stainless steel, aluminium components still weigh less than their stainless steel equivalents.

All of these properties make aluminium an ideal material for vacuum components – and Atlas Technologies’ ability to create bi-metal flanges for aluminium vacuum systems means that both researchers and industrial users can gain from the UHV and XHV benefits of aluminium.

To learn more, visit atlasuhv.com or email info@atlasuhv.com.