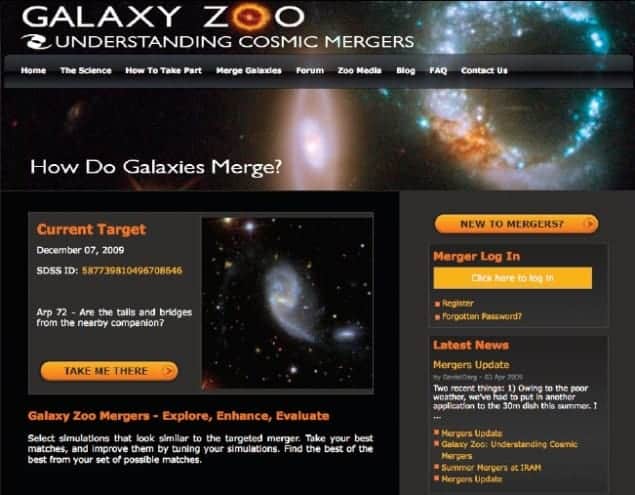

Galaxy Zoo 2 – the latest incarnation of the mass-participation galaxy hunt

So what is the site about?

Many readers will already be familiar with the Galaxy Zoo, a project that allows members of the public to trawl through images of galaxies obtained by the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS) and classify them according to their shape and features (see “Eyeballing the universe”). The image-processing power of the site’s 150,000 “citizen scientists” has already helped astronomers pick out interesting spiral and elliptical galaxies for further study. Now a new offshoot – dubbed Galaxy Zoo: Understanding Cosmic Mergers – aims to use similar “crowdsourcing” methods to enhance our knowledge of interacting galaxies.

How does it work?

Out of more than 900,000 images in the original Galaxy Zoo data set, volunteers identified about 3000 that showed two galaxies merging or colliding. Now the site’s developers want visitors to compare these real mergers with the results of collision simulations. By selecting the simulations that look most like the actual merging galaxies, and discarding those that appear different, users will be helping astronomers refine their models of how galaxies form. Weeding out “bad” simulations and highlighting “good” ones in this way might even allow researchers to estimate how much dark matter is present in the interacting regions.

What if none of the simulations look like the real thing?

“Getting a perfect result is hard,” acknowledges Chris Lintott, one of the Galaxy Zoo’s co-founders. “But getting close is easy.” If a simulation looks promising, users can “enhance” its outcome by tweaking parameters such as galaxy mass, speed and angle. This is where the real fun begins. For the most part, making a small change in, say, the mass of one or both of the merging galaxies has little effect on the result. Yet with a little tinkering, one can often find narrow regions of the parameter-space where the simulation is finely balanced between wildly divergent outcomes. In some ways, this is just a nifty trick; children of all ages will doubtless enjoy pulling and stretching their simulated galaxies into funky shapes. But it also shows just how important – and difficult – it is to develop models that offer realistic results.

Who is behind it?

The Galaxy Zoo team is a self-described “motley collection” of astronomers, computer scientists, Web developers and outreach specialists based at various institutions in the US, the UK and Europe. Prominent “Zookeepers” include Lintott, who also co-presents the BBC’s Sky At Night TV series; and Bob Nichol, a University of Portsmouth cosmologist and senior member of the SDSS. Most of them work on the site part-time, and as of early January, they are looking to hire new staff for both the technical and outreach-related aspects of the project.

How often is the site updated?

At the moment, the Zookeepers are adding a new merging-galaxy image to the site every day, although older ones will remain available for a short period so that users can revisit their favourites. If you get tired of galaxy-matching, take a look at the site’s official blog and forum, which are great places to learn more about the science behind the project and to share strategies with fellow users.

Can you give me a sample quote?

“For me, this project started 20 years ago when I was in graduate school,” writes Galaxy Zoo member John Wallin, an astronomer at George Mason University in the US. “I wrote a Fortran code to do some of this modelling work. You would set up a run, then wait hours to see the result. If it didn’t match, you had to wait hours for the next attempt…Our understanding of galaxy collisions has been limited by the lack of dynamical models…[But] with your help, we can create the models we need to understand the histories of hundreds of galaxy collisions. These models will be more reliable than any that a single scientist could create.”