Has big science killed “deep jokes”? Robert P Crease hopes not and asks for your funny tales

If you only laugh at jokes, then you’re not taking them seriously enough. Jokes have functions. “I don’t suffer from insanity – I enjoy every minute of it!” (That’s releasing stress.) “Mixed emotions is watching your mother-in-law drive off the cliff in your new Mercedes.” (That’s releasing feelings.) “Schrödinger’s cat walks into a bar – and doesn’t.” (That’s dumbing down a complex image.)

I’m not dissing such humour. Joke-telling helps us to cope. If we can laugh at something, we don’t have to feel, engage or understand it. Physics, however, has a tradition of thoughtful joke-telling that uses humorous tales inquisitively – to deepen appreciation of a person, of the world, or of both.

Jokes revealing personal characteristics have covered everything from Albert Einstein’s childlike personality and Niels Bohr’s mystique to Wolfgang Pauli’s famously brutal putdowns. Abraham Pais, for example, heard Paul Dirac enthusiastically tell (on several different occasions) a joke about a priest who is newly appointed to serve a village and is doing the rounds to get to know his parishioners. Calling on one modest home, the priest notices that the woman’s house is full of children, and asks how many children she’s got. “10 – five pairs of twins”, comes the reply. “You mean you always had twins?” asks the astonished priest. “No, Father, sometimes we had nothing.” As Pais put it: “Precision at that level had an immense appeal to Dirac.”

Too serious not to laugh

Among the jokes that reveal aspects of the world is what – or so I’m told – was the favourite piece of humour of the mathematical physicist John von Neumann. It takes place in the main square of Budapest, where a man cries out “The emperor is an idiot! The emperor is an idiot!” He is promptly arrested and carried to prison by two police officers. As they drag him away, the man begins to defend himself: “This is a mistake! I didn’t mean our emperor, I meant the Prussian emperor!” The police officers are having none of it. As the jail door clinks shut they go: “You can’t fool us! We know which emperor is the idiot!”

As for jokes that reveal both character and situation, I would include the one about the rabbinical student who goes to hear a series of three speeches by a famous and revered rabbi. When his friends ask the student what he thought about the speeches, he replies: “The first talk was brilliant, clear and simple. I understood every word. The second was even better, deep and subtle. I didn’t understand much, but the rabbi understood all of it. The third was by far the finest, a great and unforgettable experience. I understood nothing and the rabbi didn’t understand much either.” Okay it might not be a side-splitter – but according to Pais it was one of Bohr’s favourites.

Indeed, humour was never far away at Bohr’s own Institute for Theoretical Physics in Copenhagen, as Paul Halpern – a physicist from the University of the Sciences in Philadelphia – pointed out last year (Physics in Perspective 14 279). The institute hosted, for example, annual skits – the best known of which was the Blegdamsvej Faust, named after the street in front of the institute. This play was mentioned in George Gamow’s book Thirty Years That Shook Physics and was the subject of Gino Segrè’s 2007 book Faust in Copenhagen (November 2007 pp44–45).

In his article, Halpern also discusses the lesser-known Journal of Jocular Physics, compiled for Bohr’s 50th, 60th and 70th birthdays. A recurrent topic in its three volumes is complementarity – Bohr’s name for one of the most mysterious aspects of quantum behaviour – which, Halpern argues, often shares with humour itself “absurd aspects of contradictions”.

In trying to explain why members of the Copenhagen institute liked humour, Halpern says it was because jokes quite simply “spiced [up] breaks from calculation”. But are there deeper reasons? As Pais, quoting Bohr, once put it, “Some subjects are so serious that one can only joke about them.” (Having said that, I am not sure what Bohr would have said after the 2005 controversy surrounding publication, by the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten, of cartoons mocking the prophet Muhammad.)

The critical point

Jokes today tend to be short, visual and readily digestible. Type “science jokes” into Google and you’re apt to find witticisms like the one about two pieces of coal (clearly a mother and child) and a diamond, with a speech bubble from the mother saying: “Your dad’s been under a lot of pressure lately!”. That kind of joke will get a sure-fire laugh, but it passes in and out of your mind quickly without altering anything.

Once upon a time, however, science jokes were more discursive and more interesting – even in publications. In Pais’s 1988 book Inward Bound, he mentions a “Note on the quantum theory of absolute zero”, which is a paragraph-long parody of numerological attempts to derive the fine-structure constant (1/137) from the temperature of absolute zero (–273 °C). It was concocted in 1931 by three postdocs at the Cavendish Laboratory, Cambridge (Guido Beck, Hans Bethe and Wolfgang Riezler), who managed to sneak it past the editors of Naturwissenschaften (19 37); the editors were not amused when they eventually found out and published a correction.

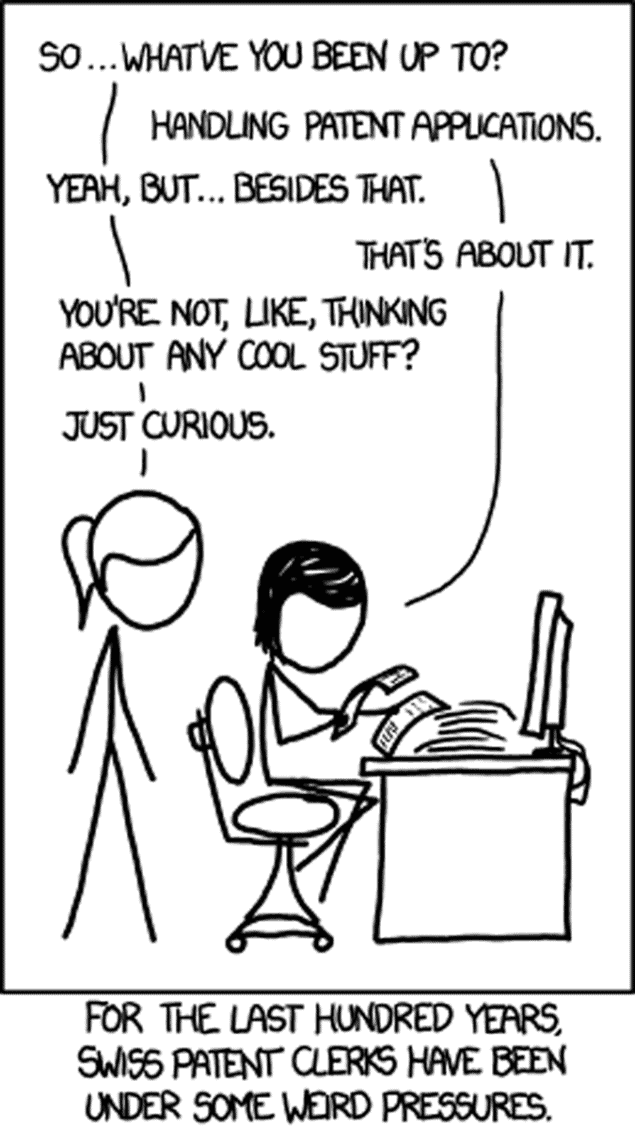

Pais called this story “arguably the best physics joke ever to slip by an editor of a first-rate physics journal”. Really? Still the best in a physics journal? (Alan Sokal’s 1996 parody “Transgressing the boundaries: towards a transformative hermeneutics of quantum gravity” was good, but it targeted a social-science – not a science – journal.) For that matter, why are the best-known examples of thoughtful humour from the era of quantum mechanics, and not from the age of string theory, dark matter and M-branes? Has big science killed deep jokes?

Please send me your suggestions of more recent humorous stories – peer-reviewed or not – to the e-mail below and I will discuss them in a future column. (But no ha-ha jokes please!)