Leonardo da Vinci died 500 years ago, but his work contains clues for how to think about the modern problem of global warming, finds Robert P Crease

Leonardo da Vinci is famed for his many, wide-ranging achievements. In science, his efforts ran from anatomy to maths. In art, his paintings are few but staggeringly beautiful. In engineering, he designed once-impractical devices – from scuba gear to flying machines – that have since been recreated, for example, at the French town of Amboise, where he died in 1519.

Da Vinci’s name, too, is a meme for the seamless integration of art and science. Witness the journal and book Leonardo, devoted to links between science and art. His work has also been extensively explored by art scholars such as Kenneth Clark, while a bestselling biography by the US writer Walter Isaacson, titled simply Leonardo da Vinci, appeared last year.

Who’d have thought, though, that da Vinci’s work could help us think about climate change? That is the fascinating suggestion of a new book by Gerard Passannante, a professor of comparative literature at the University of Maryland, US. Entitled Catastrophizing: Materialism and the Making of Disaster, it examines how disasters spur us to make productive use of the imagination – letting us grasp events that might otherwise seem to be mere abstract scientific notions.

Catastrophizing

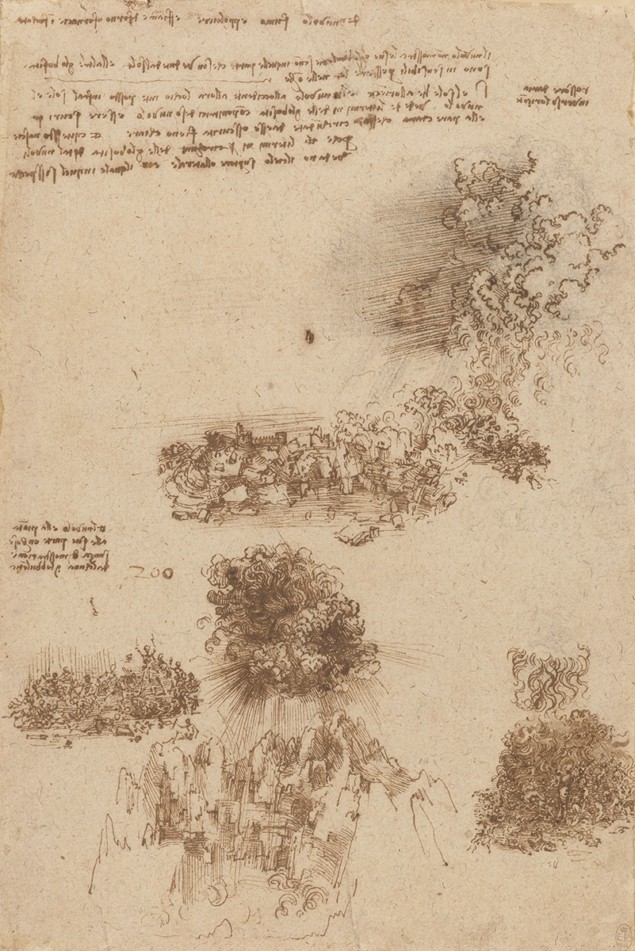

One long section of the book is devoted to da Vinci, who is famous for his depictions of catastrophes. If you’ve ever been to Windsor Castle in the UK, you might have seen 11 of his drawings of deluges that are housed there, though he also portrayed hurricanes, earthquakes, bombardments and battles. His ability to conjure up a horrifying event – and simultaneously deflate it as a physical, almost mundane occurrence – can be as jarring as a joke. Indeed, it once inspired Clark to say that the “scientific care” with which da Vinci studied “appalling catastrophes…has an almost comic effect”.

Passannante, however, finds method in da Vinci’s obsession. Until then, catastrophes were generally treated either as punishments that the gods inflicted on humans, or – increasingly – as products of impersonal natural forces that science could study. But as well as seeing disasters as objects of scientific inquiry, da Vinci approached them as images to think with. To him, catastrophes let artists cast their minds beyond the world of the sensible, to manipulate ideas of time and space, and to question our place in the universe.

In his drawings of disasters, for instance, da Vinci fastidiously followed links between nature’s enormous differences in scale. “Leonardo traced the movements of water from the smallest droplets to the largest hurricanes,” Passannante explained to me. Via his drawings and writings, the Italian approached disasters both as relentless natural phenomena and agents of suffering.

Passannante cited an example from da Vinci’s notebooks, in which the artist described the “irreparable inundation” that swollen rivers can cause, against which human protections are hopeless. “Raging and seething waves,” Leonardo wrote, can destroy dikes and levees, uprooting trees and destroying houses, “carrying these as its prey down to the sea which is its lair bearing along with it men, trees, animals, houses and lands.”

One lesson da Vinci saw in all this was humility. “Disasters make tiny creatures of us all,” Passannante reminded me. “We are no more protected than animals or insects.”

O Earth!

Da Vinci was also aware that humans can bring disaster on themselves, and are able to wreak catastrophic effects on the world. Humans bring “death and grief and labour and wars and fury to every living thing”, he wrote in his notebooks. “O Earth! Why dost thou not open and engulf them in the fissures of thy vast abyss and caverns?”

Furthermore, da Vinci exploited disasters as a laboratory in which to perceive invisible features of nature. He used sand in motion to capture violent water currents – and sawdust to indicate fierce winds. “His drawings,” Passannante explained, “capture an invisible, powerful world of hidden powers beyond what we can perceive.”

The great man also paid attention to global disasters, which to him revealed the spatial as well as temporal breadth of natural forces. “The image of the catastrophic makes visible developments that are usually beneath our attention or simply beyond a human life span,” Passannante writes. “It is as if the world were here represented in a time-lapse video.”

Disasters were, in effect, da Vinci’s thought experiments, though as much sketched out as mentally conceived

Disasters were, in effect, da Vinci’s thought experiments, though as much sketched out as mentally conceived. “We watch Leonardo turning the idea of disaster around in his mind as much as he did human anatomy,” Passannante writes, “though here this change in perspective is psychological as well as physical.”

With these experiments, Leonardo could transform a hugely dispersed, complex, and invisible phenomenon into an object of thought that he could grasp as real, not merely as a scientific concept. He used them, Passannante says, as a tool “for imagining and feeling what we can’t see with our eyes or touch with our hands.”

The critical point

So what of climate change? It, too, is a complex and vast event that springs from a global collaboration between human and natural causes. Its effects are inflicted on the human world and leave marks on nature. Climate change can hardly be approached in one fell swoop, but deploys itself across enormous differences of scale, from the tiny (lice and bugs) to the huge (oceans and the atmosphere).

Getting beneath Mona Lisa’s skin

Given the enormity of climate change, how can we think of it not as an abstract scientific finding or a future predicted development – but as a real event that needs addressing now? Though da Vinci did not talk about climate change, he modelled the kind of disaster it portends. If we are to understand a phenomenon as vast as climate change, we have to be, Passannante remarks, as “at home between shifting frames”. Like da Vinci, we have to look at climate change not only calmly and objectively, but also by letting our thinking race ahead to its possible violent extremes and terrible consequences.