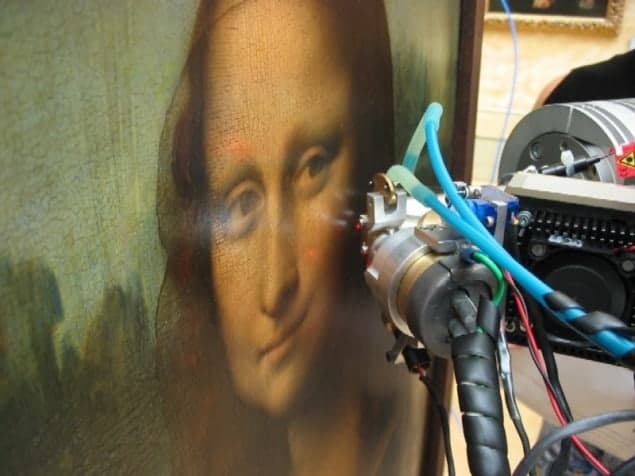

Leonardo da Vinci is revered for his ability to blend tones and colours without a brushstroke in sight, an effect that imbues Mona Lisa with such natural grace in Leonardo’s famous portrait. But, despite sharing admiration for the grand master, art historians cannot yet agree on how exactly Leonardo managed to generate this effect referred to as sfumato after the Italian “fumo” for smoke.

The uncertainty is largely because the French art authorities are, naturally, not very keen on the idea of scientists taking samples from great works of art. Now, however, a group of physicists based at the Louvre in Paris have come up with a number of answers without removing a drop of paint.

Laurence de Viguerie led a team at the centre for research and restoration of the museums of France to analyse seven paintings at the Louvre using X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy. The results confirm the reputation of Leonardo as an experimental artist who also possessed a highly dextrous hand.

Dramatic shadows

We know Leonardo’s studio had a strong culture of experimentation, but there are very few texts to describe his methods in detail. Walter Philippe

To create the natural flesh colours in the Mona Lisa, Leonardo overlaid four separate layers of paint, beginning with a priming layer of lead white and finishing with a varnish. The key to producing such dramatic shadows was to include several sublayers of glaze – with different thicknesses and with varying amounts of added pigments including iron and manganese.

“We know Leonardo’s studio had a strong culture of experimentation, but there are very few texts to describe his methods in detail,” says Walter Philippe, a member of the Louvre science team.

Recent developments in the analysis software meant that the researchers could determine the thickness of individual sublayers in the shadow, which are as thin as 1–2 µm. “Leonardo showed a great deal of skill and patience in combining his layers some of which are incredibly thin,” says Philippe.

Another celebrated artist from the high renaissance is Rafael, who is said to have learned a lot from Leonardo, having produced a lot of work in the same studio. The Louvre team intends to develop its research by using the X-ray method to look for similarities and differences in the techniques of these two renaissance artists.

“Scientific techniques provide important evidence about how the works were made, how the appearance of the works has changed over the years, and about the date and authorship of the works,” says Martin Kemp, an art historian at the University of Oxford.

“Leonardo reformed the way nature is represented according to the ‘rules’ of nature, and introduced new modes of communication between the figures in the painting and the spectator,” Kemp explained.

This research is explained in Angewandte Chemie.