As well as killing almost 3,000 people in Puerto Rico in September 2017, Hurricane Maria killed or severely damaged some 30 million trees, according to Maria Uriarte of Columbia University, US, speaking at the AGU Fall Meeting. And it broke trees in half at a rate between two and four times the amount that earlier hurricanes did.

In 1989 Hurricane Hugo hit Puerto Rico with maximum windspeeds of 120 mph whilst Hurricane Georges in 1998 brought 115 mph winds, compared to Maria’s 155 mph, Uriarte explained. The researcher has studied trees on the island as part of a 30-year programme at the Luquillo Long-Term Ecological Research site in the northeast.

Following Maria, Uriarte and colleagues visited field plots throughout the island and measured the damage suffered by each tree. By scaling up these figures, the team estimates that Maria killed or severely damaged 30 million trees, resulting in the loss of 5.28 Tg of stored carbon.

The number one risk factor predicting damage from Maria, the researchers found, was canopy height, with taller trees suffering more damage. Rainfall, not wind speed as they’d expected, was the number two risk factor, with wind speed in third place, followed by factors linked to prior rainfall and soil wetness, both of which affect tree stability.

Maria uprooted a similar number of trees to earlier hurricanes but killed slightly more, and broke between two and four times as many. The exception to this was a native palm species, which suffered similar break rates in both Maria and earlier hurricanes. Uriarte predicts that the composition of the forest could change to include more of these flexibly-trunked palms as hurricanes increase in maximum wind speed and rainfall under climate change. And forests may move from acting as a carbon sink to becoming a source under a more severe storm regime.

Maria also brought unexpectedly large nitrogen losses that lasted a long time. William McDowell of the University of New Hampshire, US, detailed how the hurricane both elevated the baseline for nitrate concentrations in Puerto Rico’s rivers and increased variability. “The wheels have come off the bus,” he said, with stream concentrations increasing and decreasing wildly in response to individual rainstorms. Those higher nitrate levels, once they reach the ocean, could cause algal blooms that smother coral reefs.

3-D view

Whilst Uriarte looked at the forest from the ground, Douglas Morton of NASA Goddard and colleagues investigated from the air, retracing the path of a survey they’d done six months before the storm. Goddard’s Lidar, Hyperspectral and Thermal (G-LiHT) airborne imager produces a 3D model of the forest by bouncing a laser beam off the trees and ground. It “can tell how many trees fall in a forest even if no-one is watching”, as Morton put it. Normally gaps from fallen trees are rare and small, but Morton’s data show that Hurricane Maria caused the equivalent of 30-50 years’ worth of tree gaps in just one day.

LIDAR also showed that Maria gave Puerto Rico’s forests “a haircut”. The storm reduced forest heights by roughly a third, created gaps in the forested area of around 10%, and damaged 55% of the canopy across the island. Morton stressed that the ecosystem is resilient and is now exhibiting lots of growth, but Maria set it on a new trajectory.

Dark skies

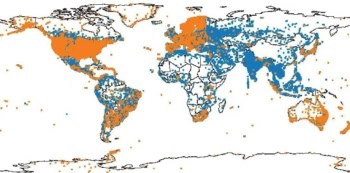

Miguel Román, also of NASA Goddard, examined Puerto Rico from even higher altitudes. He combined data for Earth at night from the Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership satellite with data from Landsat and OpenStreetMap to track where people were able to turn their lights back on across the island for the six months after Maria hit. The results showed that there was a lag between power plants being switched on and electricity access by communities. And that some communities fared better than others; at least one mountaintop community didn’t have power for a year. NASA’s Black Marble product, which can show electricity usage street by street, will be available from January 2019 for anywhere in the world; Román believes it could be useful for use in Syria or the Rohingya refugee camps.