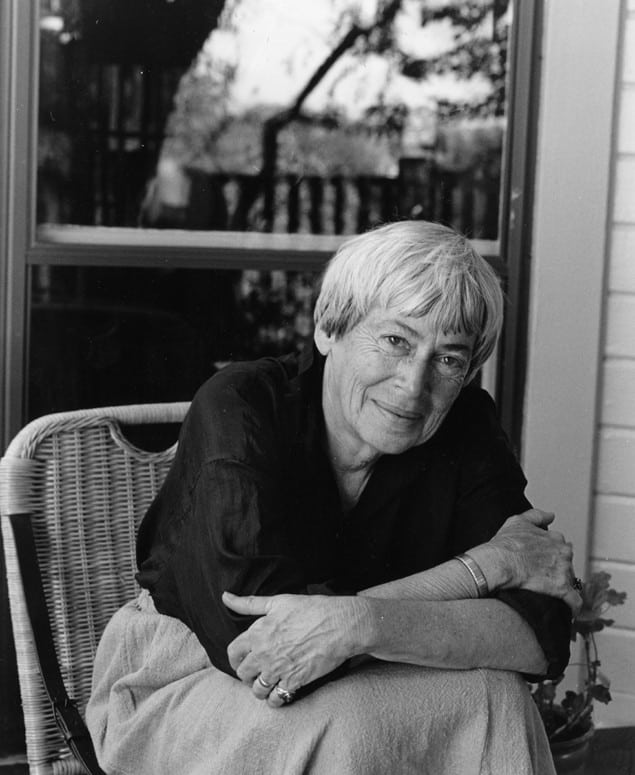

Robert P Crease pays tribute to the science-fiction writer Ursula K Le Guin, who 50 years ago introduced Schrödinger’s famous image into popular culture

The world’s most famous cat is everywhere. It appears on cartoons, T-shirts, board games, puzzle boxes and glow-in-the-dark coffee cups. There’s even a gin named after the celebrity animal. Boasting “lovely aromas of fresh mint and lemon zest”, with notes of basil, blueberries, cardamom and lemon-thyme – and “a strong backbone of juniper” – it’s yours for just £42.95 for 500 ml.

You know whom I’m talking about. But despite its current ubiquity, the fictitious animal only really entered wider public consciousness after the US science-fiction and fantasy writer Ursula K Le Guin published a short story called “Schrödinger’s cat” exactly 50 years ago. Le Guin, who died in 2018 at the age of 88, was a widely admired writer, who produced more than 20 novels and over 100 short stories.

Schrödinger originally invented the cat image as a gag. If true believers in quantum mechanics are right that the microworld’s uncertainties are dispelled only when we observe it, Schrödinger felt, this must also sometimes happen in the macroworld – and that’s ridiculous. Writing in a paper published in 1935 in the German-language journal Naturwissenschaften (23 807), he presented his famous cat-in-a-box image to show why such a notion is foolish.

For a while, few paid attention. According to an “Ngram” search of Google Books carried out by Steven French, a philosopher of science at the University of Leeds in the UK, there were no citations of the phrase “Schrödinger’s cat” in the literature for almost 20 years. As French describes in his 2023 book A Phenomenological Approach to Quantum Mechanics, the first reference appeared in a footnote to an essay by the philosopher Paul Feyerabend in the 1957 book Observation and Interpretation in the Philosophy of Physics edited by Stephan Körner.

The American philosopher and logician Hilary Putnam (1926–2016) first learned of Schrödinger’s image around 1960. “I always assumed the physics community was familiar with the idea,” Putnam later recalled, but he found few who were. In his 1965 paper “A philosopher looks at quantum mechanics” Putnam called it “absurd” to say that human observers determine what exists. But he was unable to refute the idea.

Invoking Schrödinger’s image, Putnam found that we are indeed unable to say “that the cat is either alive or dead, or for that matter that the cat is even a cat, as long as no-one is looking”. Putnam had another worry too. Quantum formalism required that if he looked at a quantum event, it would throw himself into superposition. Putnam concluded that “no satisfactory interpretation of quantum mechanics exists today”.

Enter Le Guin

It was to be another decade before the cat and its bizarre implications jumped into popular culture. In 1974 Le Guin published The Dispossessed (1974), an award-winning book about a physicist whose new, relativistic theory of time draws him into the politics of the pacifist-anarchist society in which he lived. According to Julie Phillips, who is writing a biography of Le Guin, she read up on relativity theory to make her character’s “theory of simultaneity” sound plausible.

“My best guess,” Phillips wrote in an e-mail to me, “is that she discovered Schrödinger’s cat while doing research for the novel.” Le Guin, it appears, seems to have read Putnam’s article in about 1972. “The Cat & the apparatus exist, & will be in State 0 or State 1, IF somebody looks,” Le Guin wrote in a note to herself. “But if he doesn’t look, we can’t say they’re in State 0, or State 1, or in fact exist at all.”

Le Guin was entranced by the implied uncertainties and appreciated the fantastic nature of Schrödinger’s image

Unlike Putnam, Le Guin was entranced by the implied uncertainties and appreciated the fantastic nature of Schrödinger’s image. “If we can say nothing about the definite values of micro-observables, when not measuring them, except that they exist, then their existence depends on our observation & measurement.”

In “Schrödinger’s cat”, which Le Guin finished in September 1972 but didn’t publish for another two years, an unnamed narrator senses that “things appear to be coming to some sort of climax”. A yellow cat appears. The narrator grieves but doesn’t know why. A musical note makes her want to cry but she doesn’t know for what, and thinks the cat knows but is unable to tell her. She then remembers Michelangelo’s painting The Last Judgment, of a man dragged down to hell who clamps a hand over one eye in horror but keeps the other eye open and clear. The doorbell rings and in walks Rover, a dog.

Rover pulls a box out of his knapsack with a quantum-mechanical gadget that will either shoot or not shoot the cat once it gets inside and the lid is closed. Before we open the lid, Rover says, the cat is neither dead nor alive. “So it is beautifully demonstrated that if you desire certainty, any certainty, you must create it yourself.”

The narrator is not sure. Don’t we ourselves get “included in the system”; aren’t we still inside a yet bigger box? She’s reminded of the Greek legend of Pandora, who opens her box and lets out all its evil contents. She and Rover open the lid, but find the box empty.

The house roof flies off “just like the lid of a box” and “the unconscionable, inordinate light of the stars” shines down. The narrator finally identifies the note, whose tone is now much clearer once the stars are visible. The narrator wonders whether the cat knows what it was they lost.

Le Guin’s story was soon followed by other fictional and non-fictional treatments of quantum mechanics in which Schrödinger’s cat is a major figure. Examples include the Schrödinger’s Cat Trilogy (Robert Anton Wilson, 1979); Schrödinger’s Baby: a Novel (H R McGregor, 1999); Schrödinger’s Ball (Adam Felber, 2006); Blueprints of the Afterlife (Ryan Budinot, 2012). There have also been a number of short stories including F Gwynplaine MacIntyre’s “Schrödinger’s cat-sitter” from 2001.

The critical point

Phillips called Le Guin’s “Schrödinger’s cat” a “slight, playful story with an undercurrent of sorrow”, and warned me not to overthink it. “You could think of it as ‘a fantasy writer looks at quantum mechanics’,” she explained, adding that Le Guin wrote in her journal that fantasy as a genre and physics as a science are approaches to reality that reject common sense. “I think,” Phillips concluded, “she may have been playing around with her sense, at that moment, that physics was another way of expressing the fantastic.”

If so, Le Guin unerringly found the right image.