It has all the classic ingredients of a modern, media-fuelled controversy. An unknown, young physicist makes an outrageous claim in a prestigious journal, challenging Einstein’s theory of relativity. His university issues a barrage of press-releases over the Internet. The media go wild – claims and counter-claims ensue – then the whole affair dies down, leaving the public more confused than ever about what science is really all about.

The story began when Borge Nodland from the University of Rochester in the US and his former PhD supervisor, John Ralston from the University of Kansas, published a paper in the 21 April issue of Physical Review Letters (78 3043). They had analysed data from 160 radio galaxies published by seven independent research groups before 1980, and claimed that the data showed there to be a preferred direction in space – overturning at a stroke Einstein’s view that the universe is uniform whichever way you look. This seemed dramatic enough for newspapers all over the world the to give the paper full-blown coverage.

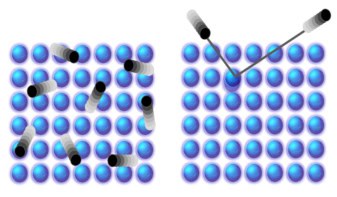

So what was Nodland and Ralston’s evidence? Many galaxies emit synchrotron radiation that is highly plane-polarized. As the waves journey through the cosmos, they pass through intergalactic magnetic fields and regions of charged particles, which rotate the plane of polarization. This is a well-known process called the Faraday effect. Nodland and Ralston claimed that the plane of polarization goes through an additional rotation – over and above the Faraday rotation – as radiation travels from a galaxy towards Earth. Their analysis appeared to show that the rate of rotation depends on the angle between the direction of the wave and a fixed direction in space. This fixed direction points roughly from Earth towards the constellation Sextans in one direction and Aquila in the other. The rate of rotation appeared to increase as a wave’s direction of travel approached this “anisotropy axis”.

Many scientists immediately reacted with scepticism, and within the space of ten days, four rebuttals had been fired off to Physical Review Letters by researchers in the US and the UK. One came from Rick Perley from the National Radio Astronomy Observatory in New Mexico and his colleagues, John Wardle of Brandeis University and Marshall Cohen from the California Institute of Technology. They claimed that much newer, high-resolution radio and optical signals – collected 2-3 years ago from 26 galaxies and quasars by the Very Large Array radio-telescope in New Mexico and the Keck Telescope in Hawaii – showed no signs of an axis of anisotropy in the universe. “Any rotation of the plane of polarization over cosmological distances was unmeasurably small and indistinguishable from zero,” they said in a statement.

“I firmly believe that Nodland and Ralston’s results do not hold up,” says Perley. “They made clear predictions that we were able to very quickly prove to be false. They stated that the plane of polarization of all distant objects would be rotated by 1-3 radians. That’s a huge signal, and trivial to measure with instruments like ours that can resolve to better than 1 degree.” Perley also says that there are hundreds of other observations made by dozens of other researchers that he could have used to show that there is no axis to the universe. “The great mystery is how Nodland and Ralston could have remained ignorant of this huge body of work,” he adds.

But Nodland believes that astronomers have attacked his work too quickly, without having thought it through. “Daniel Eisenstein from Princeton University and Emory Bunn from Bates College spoke out no more than a week after our paper was published,” says Nodland. “I would have been embarrassed to say anything as fast as they did.” And although Nodland admits that the more recent data from Perley and co-workers are interesting, he claims that the newer data must be analyzed in the same way as his original work. “I hope they do a full-blown analysis, but all they have so far done is pick out a few galaxies, and then just look at specific spots in those galaxies. They’ve also plotted different variables to the ones we did. I think they’ve misunderstood the spirit of our work – we are not claiming that every galaxy behaves in the way we predicted, just that this is how galaxies behave on average.”

One of the data sets used by Nodland and Ralston was generated by Philipp Kronberg, an astronomer at the University of Toronto, back in 1978. He also voices concern about their work. “It’s a little difficult to understand what they actually did,” says Kronberg. “The effect they claim to have seen is so amazingly large that it just cannot be true – or else people would certainly have picked up on it by now.” He points out that even if the additional polarization were true, and was perhaps related to some fundamental symmetry-breaking, it would probably be masked by other effects.

However, some critics like Ronald Bracewell and Von Eshleman from Stanford University have been willing to give Nodland and Ralston the benefit of the doubt. They have submitted a paper to Physical Review Letters proposing that the additional polarization observed by Nodland and Ralston could be to do with the absolute motion of the Sun through the cosmic background radiation, which is also towards Sextans. Nodland also says he has received several e-mails telling him of theoretical papers that show how anisotropic cosmologies are permitted within the framework of general relativity.

Another twist in the debate is that the paper was not published until two years after it had first been submitted. Nodland explains that the paper was strongly scrutinized by the referees, one of whom asked for an additional statistical analysis of the data. “The other problem was that after my PhD, I spent a year in industry, so I had no time to work on the revisions.” However, Perley thinks that there was a failure in the peer-review process. “I don’t know who the referees were but they probably weren’t familiar with radio astronomy,” he says.

Now that things have how calmed down a little, Nodland plans to respond to the various comments that have been made and has already asked Perley to send him his data. But Perley, for one, is still bemused about the media coverage. “I don’t know how such a completely wrong result could be given such prominence,” he says. He is also embarrassed by some of the statements that he and other scientists made in public. “We look like a bunch of playground kids throwing dirt at one another. I now have a higher opinion of politicians – at least they know how to talk to the press.”