The current spate of Moon missions should be a prelude to a permanent lunar base

Many physicists of a certain generation will vividly remember the excitement of NASA’s Apollo missions of the late 1960s and early 1970s when astronauts took their first tentative steps on the Moon. These heroic missions, witnessed around the world via grainy black-and-white TV pictures, captured the imagination of millions. Sadly, the public’s interest in the Moon quickly faded: the astronaut Alan Shepard even resorted to hitting a golf ball on the lunar surface in a stunt to keep that flagging interest alive. It was not until the 1990s – when NASA launched its Clementine and Lunar Prospector robotic missions – that the Moon became sexy once more.

Now everyone, it seems, wants to get in on the act. Last year the European Space Agency (ESA) celebrated the successful completion of its SMART-1 Moon mission, while Japan, China and India all have lunar projects in the pipeline (pp12–13, print version only). In addition to the political prestige that they confer, these missions serve two main purposes: they allow the countries involved to acquire scientific and technological expertise; and they help to inspire a new generation of young people to study and work in science and engineering. The missions should also yield some useful scientific information, such as data on the composition and geology of the Moon and hints as to how the solar system came into being.

It would be even better, however, if these missions paved the way to the building of a permanent base on the Moon. Apart from being a grand challenge that appeals to the human sense of adventure, such a base would let us carry out more sophisticated scientific experiments – for example examining in detail the properties of the lunar crust – and see if it is feasible for humans to live and work for several months at a time on a planetary body other than the Earth. NASA has said that it wants to build such a base by 2020, but this ambitious goal is more likely to succeed if the US joins forces with other nations to create a serious, long-term international collaboration. The current spate of lunar missions, most of which are organized at a national level, must therefore be a forerunner to a global lunar effort, in which private enterprises could even play a part.

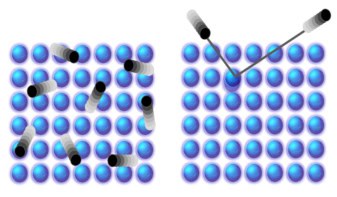

For both ESA and NASA, such a base would not be the final frontier but merely a stepping stone to something more ambitious and expensive still – sending astronauts to Mars. Since it takes so much fuel to escape the Earth’s atmosphere, most space missions can carry only relatively small payloads. On the Moon, where gravity is weaker, less fuel is needed to launch a rocket. By building up significant stockpiles of equipment on the Moon through a series of small lunar missions, the idea is that we could then send a relatively large mission to Mars, where there is exciting research to be done. But even if humans survived the trip to Mars, can we be sure that they could do anything useful once they arrived? It seems sensible also to carry out more research into new types of robots such as “self-learning” devices that can obtain information without relying on instructions sent by scientists back on Earth. We should first set up and exploit a lunar base, which would be a big enough challenge in its own right, before deciding whether to send humans to Mars.