With seven of its former pupils having gone on to win a Nobel Prize for Physics, the Bronx High School of Science is no ordinary school. Robert P Crease finds out why

Every morning about 3000 students at the Bronx High School of Science in New York pass beneath a huge mosaic that hangs over the school’s entrance. It shows a Moses-like figure – representing “the humanities” – rising over a rainbow, beneath which are tile depictions of Pythagoras’s theorem, surveying gear, a Benjamin Franklin-like key and kite, and more old stuff. The students rushing to class hardly notice. They are into calculus, photodetectors and robots.

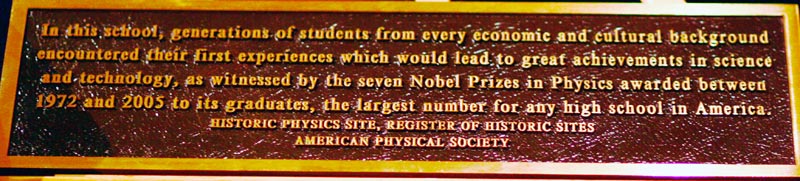

On 15 October this year, Bronx Science, as it is colloquially known, was officially designated a “historic physics site” in a ceremony organized by the American Physical Society (APS). The high school joins an imposing list of 18 other landmarks with that status. They include Bell Labs in New Jersey, where the transistor was discovered, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Radiation Laboratory, which helped to develop radar, the University of Chicago site where Robert Millikan measured the charge on the electron, and the spot outside Cleveland, Ohio, where Albert Michelson and Edward Morley did their epochal ether-drift experiment.

Located in the northwest corner of New York City, Bronx Science owes its historic status to the fact that seven future Nobel-prize-winning physicists went through its doors – more than any other high school in the world and more than most countries have ever achieved. The school, which opened in 1938, was founded by the educator Morris Meister, who believed that if a school put bright students together, it would kindle ill-defined but valuable learning processes. The school seems to have proved him right: according to the Bronx laureates, their physics learning took place mainly outside the classroom.

Roy Glauber, who shared the 2005 Nobel prize for his work on quantum optics, entered in 1938 in the school’s initial class. The first physics course was not taught until 1939, and its textbook did not even mention atoms. That subject was addressed in the chemistry textbook, which did not even say that atoms contained neutrons, despite their discovery in 1932.

A Bronx mathematics teacher changed Glauber’s life by giving him a book on calculus for summer reading, and the sophomore was thrilled to find he understood it. Glauber went to Harvard in 1942, skipped the intermediate physics courses, discovered that advanced courses were cancelled because the teachers were doing war work, and was catapulted into graduate physics. His outstanding performance caught the attention of well-connected scientists, and in 1943 – age 18 – he was spirited to the top-secret Los Alamos laboratory to help build the atomic bomb.

Leon Cooper, who shared the 1972 prize for work on superconductivity, recalls physics lessons as boring, and was far more enchanted by his biology classes, which lured him to stay late after school designing and running experiments “until they threw me out”. Indeed, the school’s basic-physics textbook was written by a certain Charles E Dull, whose work, though widely used in US high schools, lived up to his name. The future particle physicist Melvin Schwartz, who shared the 1988 Nobel gong, once told me his classmates’ excited discussions – not his teacher – were what first awakened his interest in physics.

The class of 1950 – the year below Schwartz – included Sheldon Glashow and Steven Weinberg, who shared the 1979 Nobel prize with Abdus Salam. Glashow recently told me that he cannot remember learning anything much from his introductory-physics class. At the time, the school offered only two advanced-physics courses. One was in “radio technology”, in which students built crystal radio sets, while in the “automotive physics” they took apart and reassembled an old aeroplane engine.

Neither Glashow nor Weinberg bothered with either. Far more exciting was the science-fiction club – whose members clustered around lab tables to talk about physics – and afterschool trips to the used bookstores that then populated lower Manhattan.

Particle theorist David Politzer, who shared the 2004 Nobel prize and who spoke at last month’s APS ceremony, described the school’s spirit by citing a transport strike that took place in 1966 – the year he left Bronx. The strike paralysed the city for almost two weeks and in most schools attendance plummeted; in some, nobody turned up. “[But] at Bronx Science, attendance was normal,” Politzer recalls. “We walked, bicycled and hitchhiked to school. We wouldn’t miss it!” Politzer’s classmate Russell Hulse, who shared the 1993 Nobel prize for discovering the first binary pulsar, recalled that his favourite afterschool activity was building various antennas, including a radio telescope. As Hulse told me, “It was very special to me to finally be in a place that focused on what I found most interesting and compelling in life, namely science.”

Much has changed in recent years. The advanced-physics labs were renovated last year, and “we try to instil an inquiry mindset”, says Jean Donahue, the assistant principal for science. In one physics classroom, I saw the teacher illustrate a talk on vectors by having a student navigate a blindfolded companion around the room by shouting directions and magnitudes; in another, the teacher taught the same principle by asking students how far fish swim in currents of various strengths heading in different directions.

The school’s most fearsome physics module – Advanced Placement Physics C – is tougher than most college-physics courses. Its dynamic instructor is Ghada Nehmeh, who was born in Lebanon and studied nuclear physics. Diminutive – smaller than most of her students – and scarf-clad, she jumps rapidly from lab table to lab table, helping piece together equipment and analyse results. Famous for being ruthlessly demanding, she tests the students on their first day by assigning them 40 calculus problems, due back the next day. “I’d never seen derivatives before,” says Kezi Cheng, a senior interested in theoretical physics. So Cheng did what most Bronx Science students do – she asked her classmates to give her a crash course on the subject. “They’re always willing to help.”

After last month’s ceremony, Bronx students now have a new plaque to walk past. My guess, though, is that they will be too busy scurrying to the next class to notice.