Trailblazing technologies could banish the bottleneck that comes from picking and placing myriad microLEDs, as Richard Stevenson explains

The chances are that when you watch a film, check your e-mail or surf the web, you’ll be staring at a screen populated with liquid crystals and backlit with LEDs. It’s a combination that has much merit: manufacturing costs are low, the picture is pretty good, and the display is relatively thin and lightweight – nothing like that associated with the cathode-ray tubes of yesteryear. But contrast ratios could be far higher, as could efficiencies, which would lengthen the battery life of portable devices.

Promising to address both these weaknesses is an emerging class of display that employs direct emission from red, green and blue LEDs. It is a technology that has existed for many years in magnified form, in the screens that adorn sporting stadia and a handful of prominent buildings in big cities. However, the construction of these large screens is time-consuming and costly, requiring millions of LEDs to be carefully positioned at precise locations. If this form of display is to be scaled down in size and up in volume, a new production approach will be needed to create screens based on direct-emitting microLEDs for TVs, laptops, smartphones and virtual-reality headsets.

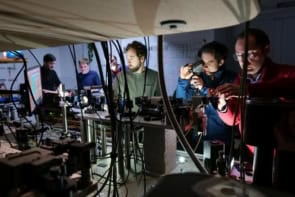

A contender for this task is the massively parallel transfer printing technique pioneered by John Rodger’s team at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. This approach uses a stamp to pick up many microLEDs simultaneously from the wafer on which they were formed, and transfer them to a backplane, sometimes via an intermediary carrier. During this process, engineers can control the distance between each of the clusters of red, green and blue microLEDs that form a colour pixel. This degree of freedom is welcome when making large screens, such as those in supersize TVs, where it is folly to have colour pixels very close together – the benefits of such a high resolution would be wasted on the viewer, while the bill-of-materials would soar.

Right now, much effort within the nascent microLED display industry is directed at accelerating the throughput of this parallel transfer process. Today, a good ball-park for pick-and-place is 50,000 devices per hour. Cutting-edge developers, such as Samsung, may be faster. But given that an ultrahigh-definition display requires 25 million microLEDs, it takes many hours to construct a display via this approach.

Maybe, even with substantial improvement, it will never be possible to produce a mass-market display with a pick-and-place approach. That’s the view of Paul Schuele, CTO of US display developer eLux. “I just don’t believe it’s going to be economically feasible, apart from for show projects,” he argues.

Microfluidic mass transfer

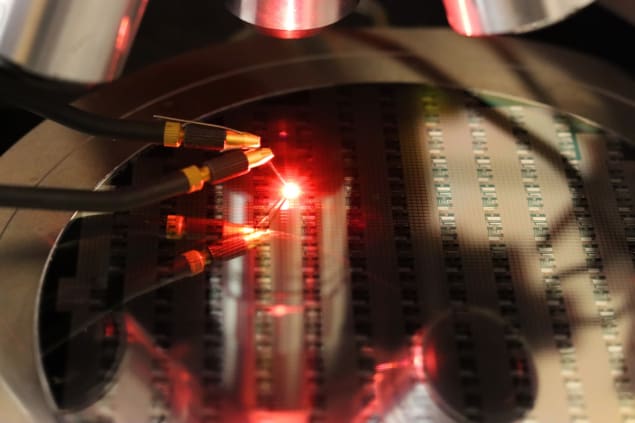

Championing one of a handful of technologies to overcome this barrier, Schuele and co-workers have developed a microfluidic process with unprecedented throughput that’s capable of placing up to 50 million microLEDs per hour. Production begins by forming batches of a novel form of LED with a circular base and a post, before suspending them in their millions in solution. This suspension is cast over the surface of a display backplane populated with an array of circular holes, each located above an accompanying thin-film transistor. MicroLEDs that fall into the holes post-up are trapped, while those that enter post-down are unstable, soon to be dislodged by the forces of the fluid (figure 1). Once displaced, those microLEDs move on. It’s not long before they are permanently trapped post-up at another site, helping to fill up all the holes in the backplane. Electrical connections are then added to every microLED, using a low-temperature anneal to unite the solder on the backplane with that on a pair of contact rings on the device. Once this connection is in place, the thin-film transistor under every microLED controls its emission.

1 Go with the flow

eLux produces microLED displays by casting a solution of microLEDs over a backplane, where they are propelled by the moving fluid. If they enter a well post-up, they are trapped; if they enter post-down, fluid forces dislodge them.

This stochastic process for populating the holes cannot, on its own, produce a colour display. To form such a display, after filling holes with blue LEDs, the red and green components for every pixel are created by adding a colour-converting medium. Quantum dots are used for this task, rather than conventional phosphors, which Schuele describes as “big grains that are nasty to deal with”. While it is possible to reduce the size of the grains, this comes at the expense of efficiency.

To simplify their display architecture, Schuele and co-workers are developing a new process that avoids the use of quantum dots, by employing direct-emitting red, green and blue LEDs. One of the challenges with this is that the red LEDs, made on gallium-arsenide substrates, are not as amenable as their blue and green cousins, grown on sapphire, to the separation of the device from its substrate. While laser-lift off can extract blue and green emitters from sapphire, red microLEDs require etching to remove their substrate. This is not easy.

Another challenge facing the makers of high-quality displays comes from the incredible sensitivity of the eye to imperfections. Commercial success hinges on eradicating defects, which, for eLux, come in three forms: an absence of microLEDs, microLEDs that are plagued by a short, and those with insufficient brightness.

Helping to address any absence of devices is a built-in redundancy, accomplished by using each transistor to drive two microLEDs in parallel. With this configuration, if one microLED is missing, it’s not an issue – there is a doubling of the current through the other microLED that masks the absence of its sibling. Unfortunately, this is not a fix for spots on the backplane where there are no microLEDs. “You can repair with pick-and-place, but my personal belief is that it is not economically viable,” says Schuele, who instead suggests a touch-up process, in which microLED solution is locally dispensed over the region with missing LEDs.

Schuele views shorts as a bigger issue, because they defeat redundancy. After identifying these renegades with thermal imaging, they can be repaired, but this is an expensive solution. So eLux prefers to identify the shorted LEDs on the device wafer and reject them.

To address the third issue – LEDs that are weak emitters – engineers screen device wafers and eliminate regions with insufficient efficiency. One powerful way to do this is to scan a focused laser beam across the wafer and record the intensity of the light emitted by the structure. Lower values expose weak LEDs.

Going forward, eLux may look to expand the range of sizes of its microLEDs. Today’s production process accommodates devices with diameters from about 150 μm to just 17 μm. Smaller sizes enable a higher pixel density and superior resolution. The current range is well suited to making TV displays, while the smaller sizes, which can easily realize a density of 300 pixels per inch, are also ideal for automotive and military displays where reliability and brightness are major assets. These microLEDs, however, are not nearly small enough for a virtual-reality headset.

The silicon solution

For that application, pixels must be no more than 5 μm in size and packed close together. It’s a pair of requirements fulfilled by another alternative to pick-and-place, being pursued by Plessey, a UK firm with a rich history in producing gallium nitride (GaN)-on-silicon LEDs.

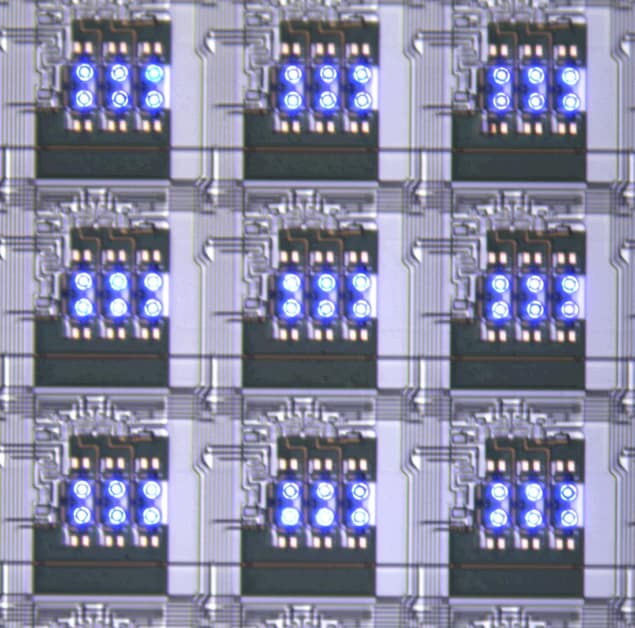

Plessey’s production process begins by growing the layers of a GaN LED on a silicon wafer. This wafer is processed to define pixels separated by blocking material, which provides electrical and optical isolation. Bonding this processed wafer to a silicon backplane creates a display, before the growth substrate for the LEDs is removed to increase light extraction.

Using this approach, Plessey forms red, green and blue single-colour displays. Those emitting in the blue and green are made from direct-emitting LEDs – the green variant is less efficient, but this is offset by the eye’s superior sensitivity in this spectral domain – whilst that in the red uses blue LEDs to pump red-emitting quantum dots, due to difficulties in creating GaN LEDs that emit red light.

The other option for the red LED is the traditional phosphide-based emitter. But this would be incredibly challenging to produce on silicon. And, according to company CEO Keith Strickland, even if successful, such effort would offer dubious reward, due to the temperature instability of this form of LED. “I’ve seen degradation on phosphide materials of 40–50% as you go up a few tens of degrees or so,” he notes. In comparison, the decline in performance of GaN-based LEDs is around just 10%, leading to improved colour stability for the display.

Customers purchasing Plessey’s single-colour red, green and blue displays can form a full-colour display by combining their output with an X-prism. It’s an approach with pros and cons: it realizes a higher resolution compared with displays that have coloured pixels side by side; but it adds weight and bulkiness.

Plessey is working towards a single-wafer solution, which requires red, green and blue LEDs to be grown in a single stack. That’s not easy, as different temperatures are needed for different emission wavelengths, and higher temperatures threaten to wreak havoc on deposited structures. However, progress has been made, with blue and green pixels produced on the same wafer. The company has also made strides at longer wavelengths, realizing a red-emitting GaN-based LED, a notoriously challenging device to produce.

To gain traction in the display industry, Plessey began by marketing its technology for assisted-reality displays, such as scuba-diving masks incorporating a dive computer, swimming googles with a lap clock and gun-scopes featuring a range finder. The publicity generated by this raised the company’s profile, and may well have played a key role in helping it to clinch a deal with Facebook, signed last March. Plessey’s technology is seen as a great fit for Facebook’s augmented-reality and virtual-reality products, such as its Oculus Quest headsets.

With such big names investing in microLED displays, the future is very bright for this technology. The approaches of eLux and Plessey clearly have much promise, giving them a great chance of competing against pick-and-place technologies and other rival approaches in a growing market that could be worth billions of dollars by the middle of this decade.