James McKenzie reflects on the possible business opportunities from future missions to the Moon and beyond

As I’m sure you’ll have noticed, this month Physics World is celebrating the 50th anniversary of Neil Armstrong setting foot on the Moon for the first time. But what I’m interested in is whether we can commercialize the Moon or use it as a “space port” to take us further afield. At first sight, that might seem mad. Space is only 100 km away, but it’s an unforgiving place, where you need to have every bit of physics, maths and engineering right to make progress.

What’s more, getting to space – and staying there – is expensive. In 2015 an Atlas V rocket launched 8123 kg into low-Earth orbit at a cost of $164m – that’s more than $20,000 per kilogram. As the joke goes: escape velocity, you can’t leave home without it. So why, apart from proving its technical prowess, why would any business bother going to the Moon? Surely it doesn’t make commercial sense?

However, as I mentioned recently, getting into orbit is gradually becoming cheaper thanks in part to the reusable rocket technology developed by former physicist Elon Musk’s firm SpaceX. Its Falcon Heavy rocket can now get 53 tonnes into low-Earth orbit for $90m – that’s barely $1700 per kg. As the European Space Agency astronaut Tim Peake has said, firms like SpaceX are “forcing technology and industry” to compete, thereby “reducing the cost of entry” to space.

Private fortunes

Another boost to space innovation has come from tech giant Google, which in 2007 began funding the Lunar X Prize organized by the US-based X Prize Foundation. Worth $30m, the prize was earmarked for the first privately funded teams to land a robotic spacecraft on the Moon, travel 500 m and transmit high-definition video and images back to Earth. Five outfits were in the running for the award, although it eventually went unclaimed after the X Prize Foundation declared that “no team would be able to make a launch attempt to reach the Moon by the deadline [of 31 March 2018]”.

Nevertheless, one of the entrants – the Israeli non-profit organization SpaceIL – continued with its efforts and this February launched a craft to the Moon. Although its craft crash-landed on 11 April, SpaceIL was given a $1m “Moonshot Award” by the X Prize Foundation in recognition of the vehicle touching the surface of the Moon, which was still an amazing achievement.

So you want to be a trillionnaire?

But perhaps it really takes governments and national pride to fund projects that are so far from being commercially viable. China certainly thinks so. It recently landed the first spacecraft on the far side of the Moon as part of its Chang’e programme (see “Exploring the far side”). The US is also accelerating its Moon efforts, with NASA boss Jim Bridenstine recently announcing that Donald Trump wants to return to the Moon and to land humans on the surface again by 2024.

Bridenstine has promised “innovative new technologies and systems” to explore more locations across the surface than was ever thought possible. “This time, when we go to the Moon, we will stay,” he promised. “And then we will use what we learn on the Moon to take the next giant leap – sending astronauts to Mars.” But there’s also a clear commercial angle too as one aim of the programme is to develop a “space economy built on mining, tourism, and scientific research that will power and empower future generations”.

X Prize founder Peter Diamandis has even predicted that the world’s first “trillionaires” will make their riches from space – not from the Moon, but from asteroids. Although one Caltech study has put the cost of an asteroid-mining mission at an eye-popping $2.6bn, remember that building a rare-earth-metal mine on our planet is roughly $1bn. Given that a football-pitch-sized asteroid could contain as much as $50bn of platinum, you can see Diamandis’s thinking.

Mining an asteroid won’t be easy. Somehow, you need to get the raw material from the asteroid, through the Earth’s atmosphere and land it without destroying our planet. And even if you can bring the stuff home, the price for the platinum could plummet if supply outstrips demand. If I were a space entrepreneur, I’d probably not bother mining asteroids unless I could find something unique and valuable enough to warrant the effort or I needed the material in space, not on Earth.

Consider water. It currently costs up to $43,000 to send a bottle of water into space, which is why it’s all recycled on the International Space Station. But there are asteroids rich in water – so if you could mine it, you could split the water into hydrogen and oxygen, which would serve as fuel and oxidizer respectively. You could even set up “fuel stations” in low-Earth orbit and the asteroid belt so that spacecraft could fill up en route to the outer planets of the solar system. About 90% of the mass of a modern rocket is fuel, so carrying less on take-off would make space flight much more affordable.

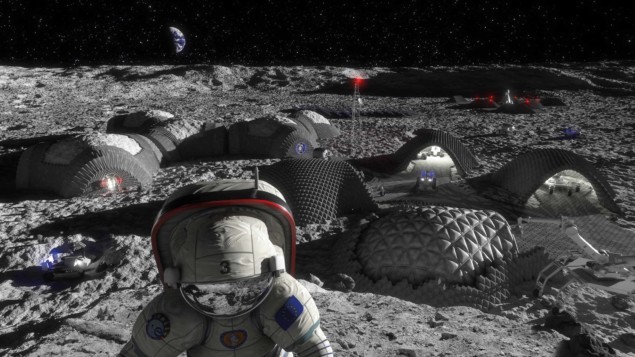

We could build a number of small robotic Moon bases to mine ice

But rather than dragging a water-rich asteroid all the way back to Earth, it may be cheaper to make rocket fuel on the Moon. Indeed, NASA’s lunar-survey missions have already found lots of ice in permanently shadowed craters on the Moon. We could even build a number of small robotic Moon bases. Each would mine ice, make liquid propellant and transfer it to passing spacecraft. Perhaps the first true commercial opportunity for the Moon will be as our first interplanetary fuel station. And wouldn’t it be great if the world’s first trillionaire were a physicist reading this issue?

- For more about the business of space, check out the Physics World online collection