For years, East Antarctica appeared more stable than the west of the continent, where the Antarctic Peninsula in particular has seen ice shelves retreat and break up.

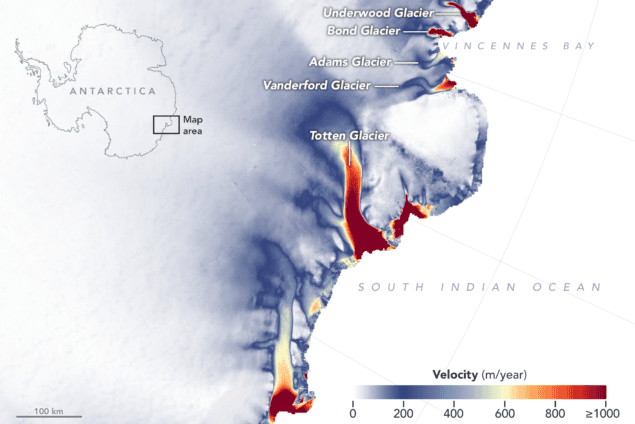

But recently scientists found that Totten Glacier, the largest glacier in East Antarctica, is retreating. And now, as Catherine Walker of NASA detailed to journalists at the AGU Fall Meeting, she’s discovered that four glaciers to the west of Totten, which had previously looked stable, are also losing ice.

These glaciers, in Vincennes Bay, have lost about 9 feet of height since 2008, Walker found using maps of ice velocity and surface height elevation. The maps are part of NASA’s Inter-mission Time Series of Land Ice Velocity and Elevation (ITS_LIVE) project. NASA will release some of this data in January 2019.

Walker also looked at model simulations of ocean temperature as well as measurements from Argo floats and seals tagged with sensors. The ocean has warmed since 1992, these data show. Walker says that waters around zero degrees in temperature are impinging on the coastline in this region now, and that’s enough to melt ice.

To the east of Totten, glaciers along the Wilkes Land coast have roughly doubled their rate of lowering since 2009; their surface elevation is now decreasing by around 0.8 feet every year. These changes are small compared to those in glaciers in West Antarctica but indicate widespread change in the east.

“Those two groups of glaciers drain the two largest subglacial basins in East Antarctica, and both basins are grounded below sea level,” said Walker. “If warm water can get far enough back, it can progressively reach deeper and deeper ice. This would likely speed up glacier melt and acceleration, but we don’t know yet how fast that would happen. Still, that’s why people are looking at these glaciers, because if you start to see them picking up speed, that suggests that things are destabilizing.”

If the Aurora subglacial basin melts that will bring 9 m of sea-level rise, whilst if the Wilkes basin melts that will raise sea-levels by 19 m, according to Walker.

There is, however, a lack of measurements around the glaciers on seafloor bathymetry, bedrock topography and hydrography, so it’s hard to predict how their melt will progress.

Observations galore

Alex Gardner of NASA JPL detailed how new satellites are coming online that will provide extra information on glacier ice. “The availability of observations will not be the limiting factor,” he said. Under ITS_LIVE, Gardner and colleagues are reanalysing optical and radar data from the last 30 years of satellite observations and bringing them together to make a more robust dataset. This puts data in the hands of researchers, Gardner said, predicting that there will be lots of observation-driven discoveries in the next five to ten years.