Laura Hiscott reviews the new television show Universe, presented by Brian Cox, which was broadcast in October and November last year and is now available on BBC iPlayer

Brian Cox’s latest blockbuster television series, Universe, has an ambitious title. In German – a wonderfully to-the-point language – the word for universe is “All”. So perhaps his show could have been called Everything. Indeed, Cox has an awful lot to get through in the five hour-long episodes. We start with Sun and stars before moving on to the search for life on other planets. The Milky Way and other galaxies are next, followed by black holes and the Big Bang.

In turning those vast, mind-bending topics into something watchable, each instalment primarily consists of dazzling CGI depicting astronomical events, interspersed with clips of Cox wandering through scenic landscapes as he explains the relevant astrophysical phenomena. While it isn’t always immediately clear why Cox has ventured to each location – apart from it offering a dramatic backdrop in keeping with the programme’s tone – each spot usually ends up serving as some sort of analogy for the physics.

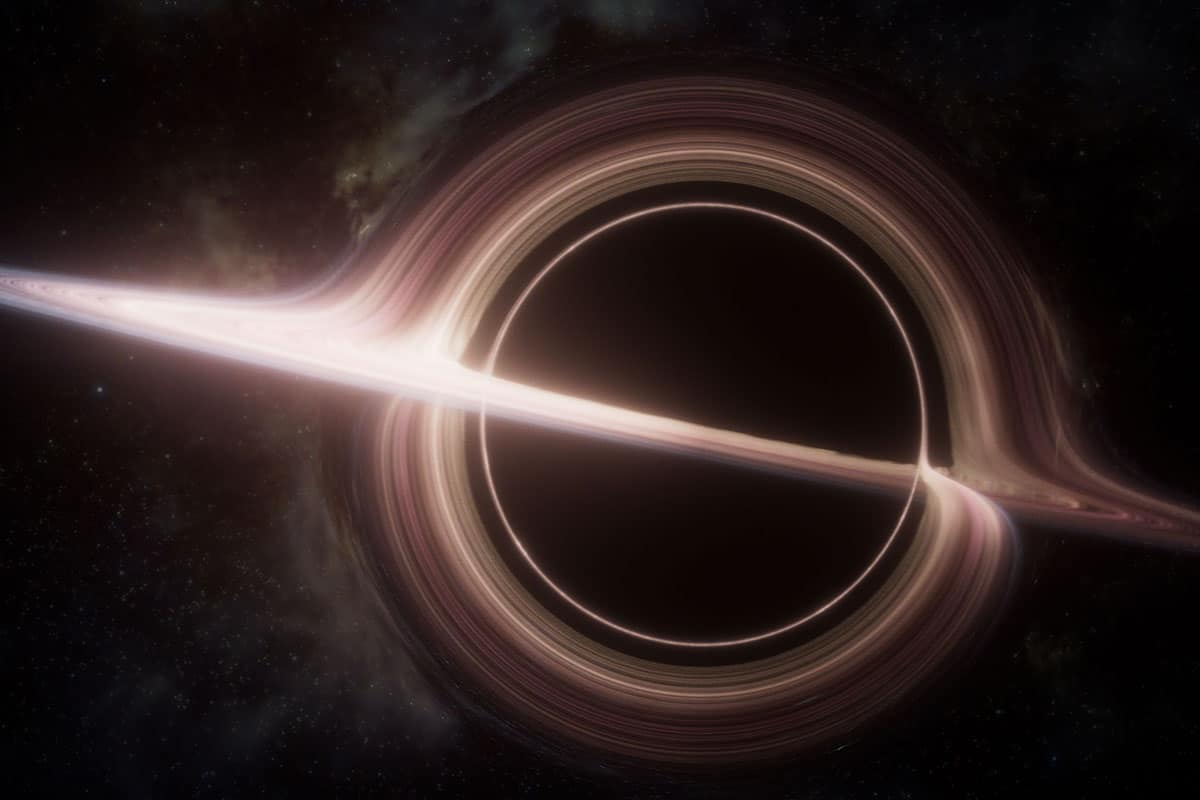

In the episode about black holes, for example, Cox walks alongside a river, describing how, in the vicinity of a black hole, the “river” of space is “flowing” towards it. If you’re far enough away, the flow of space is slow, so you can swim in the opposite direction and escape. But as you get closer to the black hole, space flows faster and faster – like the river of water as it approaches a waterfall.

Each episode concludes with a short segment about a space mission that has been investigating that episode’s subject. The one about the Sun, for instance, dedicates a few minutes at the end to NASA’s Parker Solar Probe, the closest-ever spacecraft to our closest star. Much as I admire the CGI visuals and the beautiful landscapes that make up most of the show, after 40 minutes of being immersed in them, these few minutes of space mission footage and interviews with other scientists are a breath of fresh air and a return to reality.

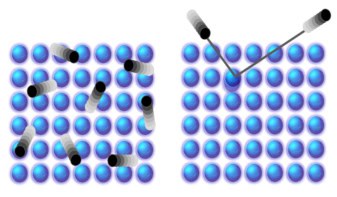

They capture the excitement of being part of a huge project with profound potential, and they inspire appreciation for the technological feats that humans have achieved to explore the universe. One scientist who works on the European Space Agency’s Gaia mission to map the Milky Way explains how the observatory takes images from opposite sides of the Sun during its orbit. The difference between them, or “parallax”, is then used to calculate an object’s distance from us (similar to how our own eyes create depth perception).

I would have loved more details like this about how we know what we know – both in terms of the techniques used and the observations that have taught us about the cosmos. The series is, sadly, light on such information, which will disappoint physicists, despite Cox touching briefly on how astronomers use redshift and type 1a supernovae acting as reference points to measure distances. In fact, I’m not sure the show will teach much new physics to someone with a background in the subject, or indeed anyone who has watched similar TV programmes before.

A few new ideas intrigued me, though. In the episode about black holes, for example, Cox suggests that having a black hole at the centre of our galaxy might have been necessary for complex life to evolve on Earth. It’s thought that the occasional outpourings of energy from the material surrounding the black hole could have reduced star formation in the outer galaxy, where our solar system lives. This would give the region greater stability – an essential ingredient for life to develop over billions of years.

The theme of life and its importance is a common thread throughout the series. In fact, I felt he labours the point, repeatedly reassuring us that, despite seeming like insignificant specks, we – as conscious matter that can think and wonder – are what gives the cosmos meaning.

Cox repeatedly reassures us that, despite seeming like insignificant specks, we are what gives the cosmos meaning

The tone is also too intense for me at times. Seemingly endless CGI scenes of exploding stars and colliding galaxies are accompanied by dramatic music as if from an epic fantasy movie. The extravagant storytelling begins right from the introduction to the first instalment – “The Sun: God Star” – where Cox explains how we are drawing “ever closer to being able to tell what is surely the greatest story ever told”.

Two scientists’ debate over whether the universe had a beginning – and how the elements were created

The theatrics peak in the fourth episode with the anthropomorphizing of black holes. As Cox details the growth of the Milky Way’s central black hole, Sagittarius A*, he describes it as developing “a taste for more massive prey” and says it “cannibalized its cousin” when it collided with a similar object. But later, after hearing that its presence might have been necessary for our own existence, we are presented with CGI depicting Sagittarius A* while the accompanying song’s lyrics plead: “I’m just a soul whose intentions are good; Oh Lord, please don’t let me be misunderstood.”

The cynic in me felt that moments like this bordered on overkill. And yet, after watching the final episode I did find myself looking again at astronomical images with a renewed sense of wonder. As one scientist says in a segment at the end of the last episode, “It’s really hard to remember what it was like before we had the Hubble Space Telescope. We’ve gotten so used to these extraordinary photographs.”

As humans living our daily lives, we are bombarded with so much new information that even the most incredible facts cease to amaze us after quite a short time. But I think it’s worth it to occasionally revisit them as if you had never learned them before.

Sure, Universe sometimes feels a bit over the top. But as Cox reminds us, there are over two trillion galaxies in the universe, each with hundreds of billions of stars. How do you even begin to convey that without coming across as a bit over the top? If you just want to be wowed by all the ridiculous magnificence of it then that’s a perfectly legitimate pastime – and this programme is for you.

- BBC 2021