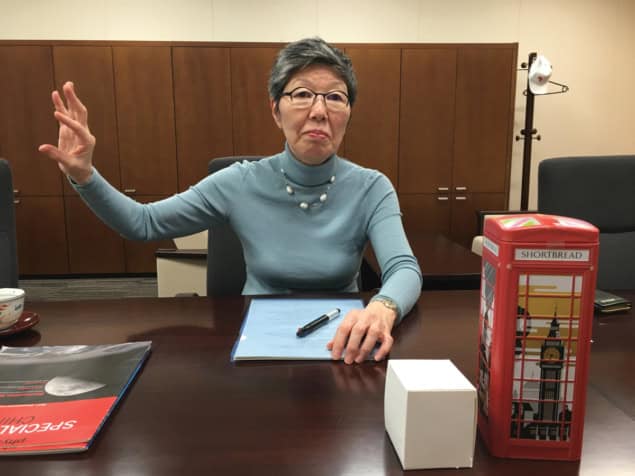

As a member of Japan’s Council for Science, Technology and Innovation, which advises the prime minister Shinzo Abe and formulates policies on science, Yuko Harayama talks to Physics World about how the country is aiming to boost research and drive innovation

Could you tell us about your background?

I have spent half of my life outside Japan. I left the country when I was 14 years old and moved to France. I did a BSc in mathematics at the University of Besançon in 1973 but then stopped my studies to focus on having a family. After moving to Switzerland in 1983, I became interested in the economic aspects of the education system and completed a PhD in economics at the University of Geneva in 1997. I moved back to Japan in 2001, where I spent more than a decade working as a professor at Tohoku University. I was appointed as an executive member of the Council for Science, Technology and Innovation (CSTI) by prime minister Shinzo Abe in 2013.

When was the CSTI created and what are its main activities?

In the 1990s Japan’s economy was struggling and the government was seeking a way to recover. One such action was to invest in science and technology. In 1995 politicians created the “science technology basic law” to begin that investment boost in these areas. A bylaw of this was the creation of a Council for Science Technology Policy (CSTP). In 2014 we then decided to modify the law to add “innovation” into the official name.

Does that mean your focus is now on innovation?

Our main focus is on innovation driven by science and technology rather than just purely entrepreneurial business models. Our biggest task is preparing the five-year science and technology plans – the so-called Science and Technology Basic Plan – which take almost a year to carry out. We are also currently involved in preparing next year’s budget where we coordinate all the spending on science, technology and innovation.

How many people sit on the council?

There are eight executive members. We try to have a gender balance. It is not written in law, but from the beginning we used to have two women among the eight, which is not so bad in a Japanese context. We also try to have a balance between people from academia and the private sector.

How are members of the council selected?

We have two categories of members. The first is politicians. For example, the prime minister is the chair of the council and we also have other relevant government ministers, including the minister of finance. Then there are the executive members, like me. There are eight executive members, of whom seven are political appointees – as such, you receive a call one day, asking if you want to be part of the council. The remaining seat is reserved for the president of the Science Council of Japan.

How often does the prime minister attend the meetings?

When we need to have a meeting, we ask the prime minister’s office to set one up. This is defined by the prime minister’s schedule. On average, we have one every two months.

How is your work organized? Does the prime minister come to you with an initiative?

In the past, when a big question arose, he would ask the council to prepare a report. But recently, we have had more power and we can propose topics and policy for the prime minister to consider.

What kind of things have you pushed towards him recently?

Before Abe became prime minister, the council didn’t have any budget for itself that it could allocate for projects. So we proposed our own budget that would allow us to create our own programmes aimed at bringing policy innovation. After a long negotiation, we finally succeeded.

Is the prime minister a good supporter of science? Does he understand the value it brings?

The strength of the council is that it is chaired by the prime minister and in that regard he is very supportive. I think he’s confident that we are doing our jobs correctly.

Japan’s spending on science has been reducing, why is this?

It is not quite reducing, but staying at the same level. Each time we propose a new annual budget for science and technology we try to increase spending, but we have not been very successful recently due to the fierce competition among policy priorities, in particular social security. Japan spends almost 4% of its gross domestic product (GDP) on science and technology so we are quite good compared with other countries. Yet not even 1% of that is from the public sector. Our goal is to have at least 1% from the public sector and also push the private sector so we spend more than 4% of GDP on science. That’s the negotiating position, but we have to bear in mind the socio-economic situation in Japan, especially with an ageing society and ever-increasing public debt.

Would you consider Japan to be more innovative compared with China or Korea?

If you look at data related to innovation, we have fallen behind Singapore, China and Korea. I am impressed by the developments coming from these countries. They are quicker to react and also take action on the ground.

Since the Fukushima incident in 2011, how has giving scientific advice changed in Japan?

Before Fukushima, when the government needed to act it formed a committee of experts in that particular field, for example nuclear power. What we recognized after Fukushima is the need to have experts from a wider breadth of areas rather than just one selected field. We also decided not to have one person assigned as a chief science adviser – as some other countries have – and let our council play that role.

Is it a problem that Japan struggles to attract foreign researchers?

We are pushing to increase the proportion of foreign researchers and we have funding to do so. So we want more exchanges, particularly for students. We find that many researchers who come here also love Japanese culture. They’re happy to come to really experience Japanese life and at the same time do science. Yet there are difficulties, notably with social life and family issues. International school, for example, is unaffordable for someone on a university salary. So there are many things we need to think about.

Is the International Linear Collider going to come to Japan?

I know some are working on that and the Science Council of Japan has been recommended to identify its location, but it takes time. It’s not only a scientific endeavour, but a political one too. There needs to be a consensus to set up such large infrastructures and to help set up all of the related issues such as finance and governance structure.