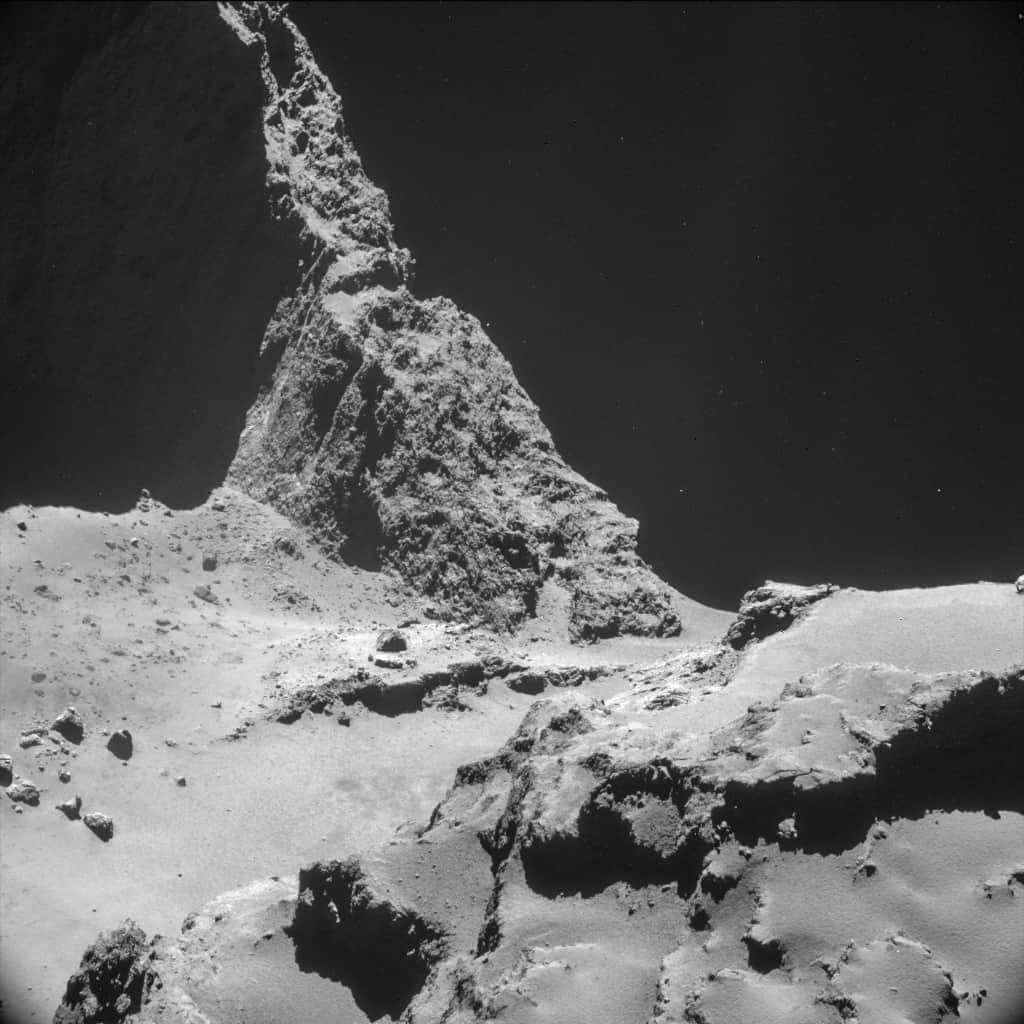

(Courtesy: ESA/Rosetta/NAVCAM, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO)

By Tushna Commissariat

Last week was exciting and exhausting for anyone involved in space exploration and astronomy, after scientists working on the Rosetta mission of the European Space Agency (ESA) made history when their “Philae” module touched down safely on the surface of comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko. But soon after celebrating Philae’s successful landing, a dramatic story unfolded. With a bumpy triple landing, harpoons that did not fire and tether the probe, as well as a final resting spot that lay in the shadows, which meant its solar panels received very little sunlight, Philae’s tumultuous story captivated the interest of thousands of people across the globe.

In the early hours of Saturday morning, as Philae’s batteries slowly drained of power, thousands mourned. “So much hard work..getting tired…my battery voltage is approaching the limit soon now,” Tweeted the Philae crew, and yet, the lander’s story was ultimately happy and successful. Although it spent only 57 “active” hours on the comet, ESA mission scientists were happy to report that the lander had indeed completed the entirety of its primary science mission.

According to a Rosetta mission update, the lander “returned all of its housekeeping data, as well as science data from the targeted instruments, including ROLIS, COSAC, Ptolemy, SD2 and CONSERT. This completed the measurements planned for the final block of experiments on the surface.” This achievement means that the relatively lightweight Philae lander actually managed to drill into the comet using the SD2 instrument, despite not being screwed in to the surface, and retrieve a sample – a formidable and risky task. The Rosetta team also managed to move the lander – lifting its body by about 4 cm and rotating it by about 35° to try to get some more solar energy – although as the last science data fed back to Earth, Philae’s power rapidly depleted.

“It has been a huge success, the whole team is delighted,” said Stephan Ulamec, lander manager at the DLR German Aerospace Agency. “Despite the unplanned series of three touchdowns, all of our instruments could be operated and now it’s time to see what we’ve got.”

Members of the Rosetta team now have heaps of science data to trawl through for new findings, and they are still searching through the many high-resolution images from the orbiter for Philae’s still unknown final resting spot. While descent images show that the surface of the comet is covered by dust and debris ranging in size from millimetres to metres, panoramic images taken by Philae tell a slightly different tale – you can see layered walls of harder-looking material. “We still hope that at a later stage of the mission, perhaps when we are nearer to the Sun, that we might have enough solar illumination to wake up the lander and re-establish communication, ” added Ulamec.

One of the interesting bits of science to have already emergde from Philae’s experiments came from the Multi-Purpose Sensors for Surface and Subsurface Science (MUPUS) instrument that was activated on Friday. MUPUS has a hammer of sorts that intended to smash through 67P’s surface and look at what lies beneath. Interestingly, however, the device kept hammering away at the surface with all its might for nearly seven minutes to no avail – despite being ramped up by the scientists to what they describe as “a secret power setting 4, nicknamed ‘desperate mode’“. In fact, the hammer eventually gave up and failed. This observation is intriguing as everything we thought we knew about the comet suggested that its surface was not quite that hard. Indeed, the MUPUS team jokingly Tweeted that “MUPUS performed beautifully inside the specifications. The comet failed to cooperate.”

Philae is now “hibernating” and will continue to do so until more sunlight falls on its solar panels, which may happen in August next year as the comet approaches the Sun and becomes much more active. Until then, the main Rosetta spacecraft will remain in orbit around the comet and continue its mission to study the body in detail as the comet becomes more active.

“At the end of this amazing rollercoaster week, we look back on a successful first-ever soft-landing on a comet. This was a truly historic moment for ESA and its partners,” said Fred Jansen, Rosetta mission manager. “We now look forward to many more months of exciting Rosetta science and possibly a return of Philae from hibernation at some point in time.”

While Philae snoozes on the alien world that is comet 67P, I can’t help but notice just how attached people have become to the lander over the last week. Maybe it was fuelled by the rather touching Tweets that Philae and the Rosetta mission sent out, or the sheer challenges involved. But I and many others have anthropomorphized the lander and, for three days, thousands of people worried about the outcome of a scientific experiment nearly as much as the scientists themselves did. We fretted when the scientists in the control room looked worried, we cheered when they received a signal from 511 million kilometres away and we sent little messages of luck and hope to a washing-machine-sized box that set off on a journey 10 years ago. As Jonathan Freedland, writing for The Guardian, said, “If Philae expires on the hard, rocky surface of Comet 67P the sadness will be felt far beyond mission control in Darmstadt, Germany.”

I can only contemplate how high emotions ran across the globe when the first Moon landing took place. I for one truly enjoyed sharing my usual joy and excitement about science with so many people all over the world and I look forward to a Tweet from Philae sometime next year.