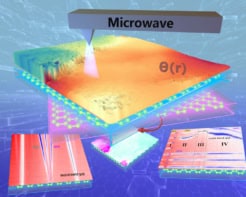

Researchers at Duke University in the US have developed a cheap and easy-to-construct thermal camera that can capture a multispectral image half a million times faster than existing broad-spectrum detectors. The new camera owes its speed to advanced plasmonic and pyroelectric materials, and its inventors say it might find applications in medicine and food inspection as well as the up-and-coming field of precision agriculture.

Thermal cameras can sense radiation across a wide range of frequencies within the electromagnetic spectrum, but they suffer from relatively slow response times, on the order of a few milliseconds. They are also bulky, difficult to make and can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Now, researchers led by Maiken Mikkelsen have constructed a new type of photodetector that can be integrated into a single chip, and is capable of recording a multispectral image in just 700 picoseconds (10-12 s). With a potential cost of just $10 in terms of the materials employed, the device is also a fraction of the price of conventional thermal cameras. These are costlier, among other reasons, because of the expensive materials used in their lenses, which are usually made of germanium.

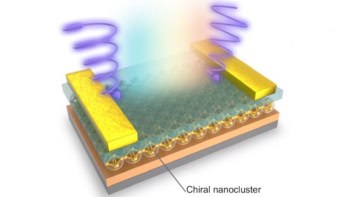

Plasmonic metasurface and pyroelectric thin film

The new camera contains a metallic material with a structure that can be fine-tuned to interact with light in very specific ways. It works by exploiting the physics of plasmons, which are quasiparticles that arise when light interacts with the electrons in a metal and causes them to oscillate. The shape, size and arrangement of nanoscale structures within so-called plasmonic materials make it possible to support plasmons at specific frequencies. Hence, by adjusting these structural parameters, the researchers can dictate which frequencies of light the material will absorb and scatter.

In the Duke group’s camera, the plasmonic metasurface is made from silver cubes a few hundred nanometres in size. These cubes are placed a few nanometres above a layer of gold (just 75-nm thick) that rests on a thin film of aluminium nitride (105-nm thick). The aluminium nitride is a pyroelectric, meaning that it produces a voltage when it is heated.

When light hits the surface of a nanocube in the thermal camera, it excites the electrons in the metal, trapping the light energy at a frequency that depends on the size of the nanostructure and its distance from the base layer of gold. The heat from this trapped light energy is enough to change the crystal structure of the pyroelectric aluminium nitride below the nanocube, creating a voltage that can then be measured.

Fast process

This process is very fast because over 98% of the light falling on the camera is converted into localized surface plasmons that are confined between the silver nanocubes and the gold film. These plasmons decay in just femtoseconds (10-15 s), generating heat through the scattering of electrons with vibrations of the material lattice (phonons) – a process that takes several picoseconds. This heat then quickly diffuses though the gold film into the underlying aluminium nitride, again in just tens of picoseconds.

For the camera in this work, which is described in Nature Materials, Mikkelsen and her colleagues constructed four photodetectors, each tuned to respond to wavelengths of between 750 and 1900 nm. In principle, however, the researchers could create systems that would respond to frequencies ranging from the ultraviolet region (by substituting platinum, silver or aluminium for the gold layer) to the mid-infrared (by fabricating larger nanocubes and adjusting the spacings between them).

Although photodetectors with pyroelectric materials have been made before, and commercialized, these earlier devices could not focus on specific electromagnetic frequencies. This, coupled with the fact that thick layers of pyroelectric material were needed to produce a sufficiently strong electrical signal, meant that they operated at much slower speeds. The new plasmonic detector can be tuned to specific frequencies and traps so much light that it generates a lot of heat. “That efficiency means we only need a thin layer of material, which greatly speeds up the process,” says study lead author Jon Stewart.

A host of applications

Mikkelsen and colleagues believe the new device could have a host of applications. Physicians, for instance, might use a fast, cheap multispectral imager to measure the spectral “fingerprint” of a biomedical sample, and thereby distinguish between cancerous and healthy tissue during surgery. Food safety inspectors might use the device to determine whether a food sample contains harmful contaminants, such as bacteria.

Thermal imaging monitors radiotherapy efficacy

Another important area is precision agriculture. To the naked eye, a plant may simply appear green or brown, but Mikkelsen notes that the light reflected from its leaves at frequencies outside the visible part of the spectrum contains a cornucopia of valuable information. Multispectral images of plants might indicate the type of plant and its condition, such as whether it needs watering, is stressed or has a low nitrogen content, which would indicate that it needs more fertilizer. “It is truly astonishing how much we can learn about plants by simply studying a spectral image of them,” she says.

Hyperspectral imaging could thus allow farmers to apply fertilizer, pesticides, herbicides and water only where needed, saving valuable resources, reducing costs and pollution. For example, a camera might be mounted on an inexpensive drone that maps a field and transmits that information to a tractor designed to deliver fertilizer or pesticides at variable rates across the field, Mikkelsen adds.