Installing large amounts of wind and solar power in the Sahara Desert and neighbouring Sahel would increase local temperatures, rainfall and vegetation. That’s according to climate modelling by a team from the US, Italy and China.

“Previous modelling studies have shown that large-scale wind and solar farms can produce significant climate change at continental scales,” says Yan Li of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, US. “But the lack of vegetation feedbacks could make the modeled climate impacts very different from their actual behaviour.”

With that in mind, Li and colleagues included vegetation response in their models. They were among the first to take this approach for wind and solar farms.

The simulated renewable energy plants would cover more than 9 million square km; the wind farms would generate an average of around 3 terawatts of electrical power and the solar farms around 79 terawatts.

“In 2017, the global energy demand was only 18 terawatts, so this is obviously much more energy than is currently needed worldwide,” says Li.

Wind farms warmed near-surface air temperatures in the region, the model showed, changing minimum, i.e. night-time, temperatures more than maximum temperatures. Wind turbines enhance vertical mixing, potentially bringing down warmer air from above.

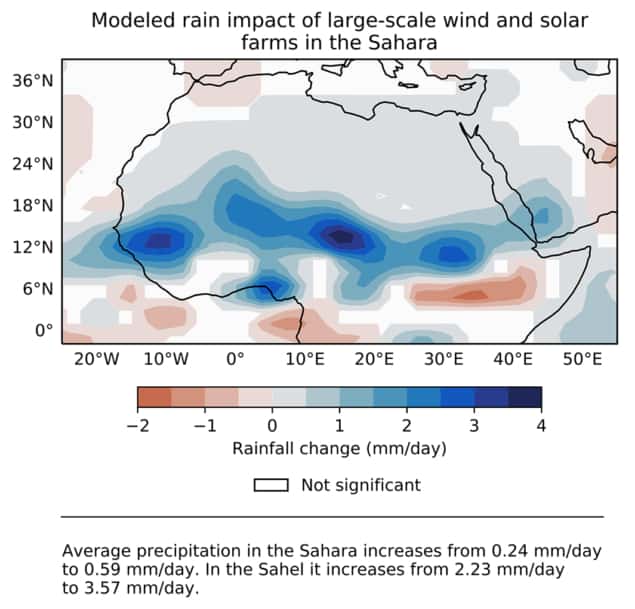

Precipitation also increased as much as 0.25 mm per day on average. “This was a doubling of precipitation over that seen in the control experiments,” says Li. “This increase in precipitation, in turn, leads to an increase in vegetation cover, creating a positive feedback loop.” In the Sahel, average rainfall rose 1.12 mm per day where wind farms were present.

Solar farms also boosted temperature and precipitation in the models. Solar panels with a conversion efficiency of 15% reduced the albedo — reflectivity – of the land surface so that it absorbed more heat, increasing rainfall by around 50%. Solar panels with an efficiency of 30% would have a negligible effect on albedo, according to the team.

“The increase in rainfall and vegetation, combined with clean electricity as a result of solar and wind energy, could help agriculture, economic development and social well-being in the Sahara, Sahel, Middle East and other nearby regions,” says Safa Motesharrei of the University of Maryland, US.

The team focused on the Sahara because it’s the largest desert in the world, sparsely inhabited, highly sensitive to land changes and “is in Africa and close to Europe and the Middle East, all of which have large and growing energy demands”.

The team reported the findings in Science.

- This article was based on a press release from the University of Illinois, US.