Yesterday, scientists working on the Rosetta mission of the European Space Agency (ESA) made history when their “Philae” module touched down safely on the surface of comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko. Since then, the mission scientists have been in communication with the lander and it has emerged that Philae bounced twice, moving nearly 1 km back out into space, and that it touched down on the comet three times before settling at a location nearly 1 km away from the target site. Its current position is precarious and does not provide its solar panels with enough light to operate as planned. Despite its rocky landing, some instruments on Philae are running and the team says it is continuing to receive “great data and images”.

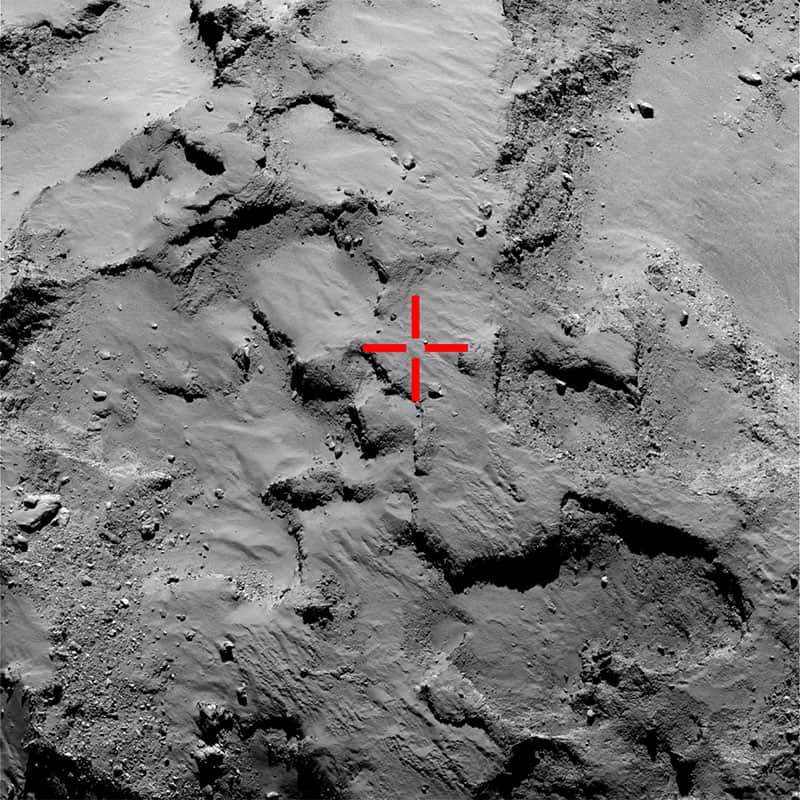

Philae first landed yesterday at 15:33 GMT before it bounced up and touched down again at 17:26 GMT, then bounced up once more, finally coming to rest at 17:33 GMT. It settled on the comet surface at a currently unconfirmed location, about 1 km from its target site. The multiple bounces are likely to have occurred because the lander’s harpoon, which should have anchored Philae onto the surface, did not fire. The lander’s position is also precarious, as initial data and images show that it has settled in the shadow of a cliff. It currently has one of its three feet in “open space”, rather than on the surface. Although Philae’s ultimate location is less than optimal, its first landing spot – seen in the image above that was taken by the OSIRIS instrument on Rosetta from a distance of 30 km in September – was right on target.

Bizarre orientation

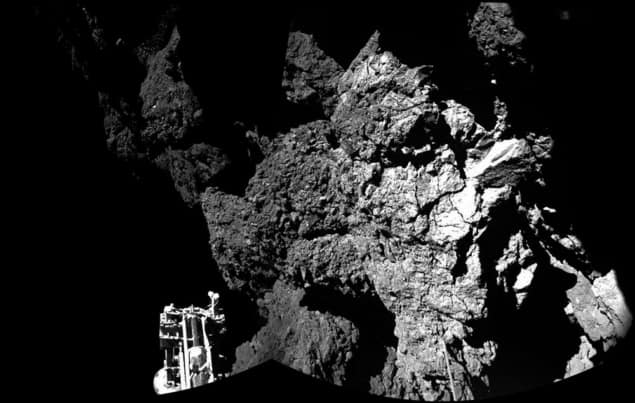

In a press briefing held today, Stephan Ulamec, who is the project manager for the lander, said that panoramic images from Philae suggest that it is on the far side of a large crater in the previously considered but ultimately rejected landing site B. According to Ulamec, this would explain the lander’s “bizarre orientation”. This location also means that Philae’s solar panels are not getting as much solar radiation as anticipated, forcing the module to run on its batteries, which should last for about 60 h. “The lander is relying on solar energy…we’re getting one and half hours of sunlight when we expected six or seven. This has an impact on our energy budget,” said Ulamec.

Although it is currently stable, Philae is not fixed to the surface because of the failure of its harpoons. Trying to “refire” the harpoons at this stage could be an even riskier business as the procedure could throw the lander back out into space.

Ulamec also said that the team would have to be wary about carrying out one of its main scientific objectives – drilling into the comet to collect and analyse samples – because this could affect the lander’s stability and tip it over. Thankfully, Philae was designed to achieve this, along with its other key objectives, within its initial 60 h battery life, which will end by Saturday. Jean-Pierre Bibring, who is the chief scientist for the lander, said that studying the organic and isotopic compositions of such samples is key and that there are a few instruments at Philae’s disposal that could achieve that goal.

While Bibring was hopeful that they could get the green light to begin drilling tomorrow, he also cautioned that they “don’t want to start drilling and end the mission”, so it is more likely that the Rosetta scientists will take a chance on drilling towards the end of the 60-hour period.

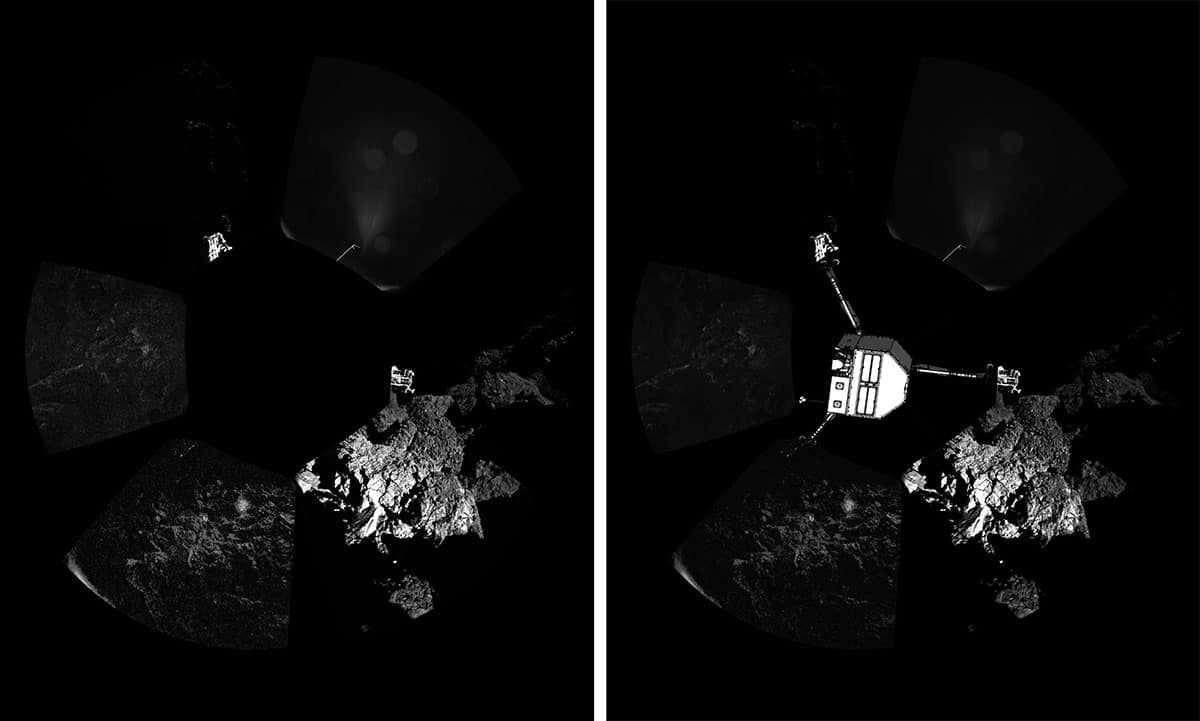

Despite the many issues that the Rosetta scientists are trying to resolve, Philae is already relaying a wealth of data. It has acquired the magnetic-field measurements of the comet and has been “sniffing” its surroundings. The image above was taken by Philae’s Rosetta Lander Imaging System when it was 40 m above the surface. The close-up shows a loose, dusty surface covered in rocks that range from millimetres to metres in size, according to Stefano Mottola from the Lander Control Centre in Cologne, Germany. He also pointed out the small fuzzy patch near the top right hand corner of the image, saying that it showed an active process on the comet with “the dust being mobilized” near the small rock. Although this initial site showed the “dirty snowball” image we have of comets, Philae’s current spot shows a rather hard, rocky surface, giving the researchers plenty to ponder on.

The next 36 hours will be absolutely crucial to Philae’s mission as the team attempts to carry out all of its main objectives, manoeuvre it out of the shadows and try get its third foot to touch the ground.