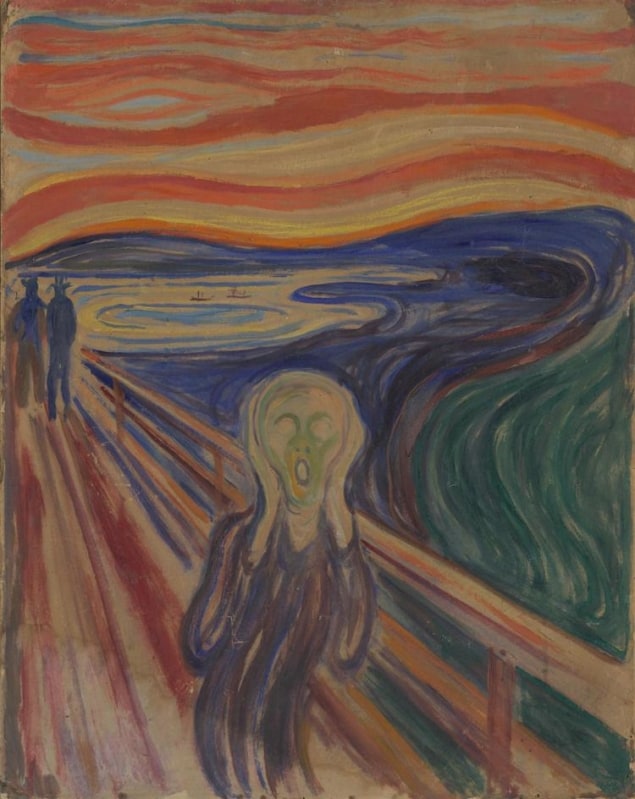

Edvard Munch’s painting The Scream (ca. 1910) is often described as the ultimate expression of the anxiety-ridden existence of modern man, but after more than 110 years, this evocative artwork is showing its age. The degradation is especially severe in areas where Munch used cadmium-sulphide (CdS)-based pigments, and the painting has become so delicate that it is rarely exhibited, remaining instead in a protected storage area in the Munch Museum in Oslo, Norway. An international team led by researchers at the National Research Council (CNR) in Italy have now used a combination of in-situ non-invasive spectroscopic and synchrotron X-ray techniques to show that moisture is the main cause of the degradation. According to the Munch Museum’s Irina Crina Anca Sandu, the team’s work could help conservation experts develop new conservation strategies to better preserve this and other works of art.

Munch created several versions of his masterpiece: two paintings, two pastels, a series of lithographic prints and several drawings and sketches. The most familiar are two paintings, created in 1893 and around 1910, which belong to the National Gallery and the Munch Museum, respectively.

The Scream is considered Munch’s most central work of art, and its impact comes from his intensive use of rhythmic wavy lines and contrasting straight bands typical of the Art Nouveau period. In The Masterworks of Edvard Munch (Museum of Modern Art, 1979), Munch is quoted as saying: “I walked one evening on a road—on the one side was the town and the fjord below me. I was tired and ill—I stood looking out across the fjord—the sun was setting—the clouds were coloured red—like blood—I felt as though a scream went through nature—I thought I heard a scream—I painted this picture—painted the clouds like real blood. The colours were screaming.”

Some screaming colours have chemically transformed

To make the “screaming” colours, Munch experimented with combinations of diverse binding media (tempera, oil and pastel) and brilliant and bold synthetic pigments such as zinc white, Prussian blue, synthetic ultramarine blue, chrome yellow and green, and cadmium orange and yellow. He did not know, however, that these novel materials would chemically transform over time, altering in colour or becoming structurally damaged. Today, some yellow areas of the sunset cloudy sky, as well as the neck area of the central figure in the ca. 1910 painting, show clear signs of degradation: the cadmium yellow brushstrokes have become off-white, and the lake water, which Munch thickly painted with opaque cadmium yellow, is flaking.

Earlier studies that applied scanning electron microscopy-energy dispersive X-ray and Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) techniques to microsamples of The Scream revealed that cadmium carbonate makes up most of the paler yellow tones of the sky and the main subject’s neck. These studies also showed that the cadmium carbonate had been mixed with varying amounts of sulphur, chlorine and sodium compounds in the lake region of the painting.

These observations, however, left the CNR-led team with several unanswered questions. Was the extent of the degradation in the CdS-based paint surface linked to its chemical composition? Into which compounds had the cadmium yellow compounds degraded? And finally, what caused these paints to deteriorate?

Non-invasive spectroscopy and synchrotron radiation X-ray techniques

To answer these questions, the researchers studied selected CdS-based areas of the painting using a series of spectroscopic analyses through the European MOLAB platform – a network of facilities from Italy, France, Poland, Greece and Germany that provides portable equipment for in-situ non-invasive measurements on artworks. They combined these analyses with the study of micron-sized samples from the painting that they obtained by scraping off an area from a spot of the flaking yellow surface of the lake region. They analysed these minute samples using micro X-ray diffraction, micro- X-ray fluorescence and micro X-ray absorption near-edge structure spectroscopy, mainly at the ID21 beamline at the ESRF (the European Synchrotron) in Grenoble, France. “This beamline is one of the few in the world where we can perform imaging X-ray absorption and fluorescence spectroscopy analysis of the entire sample at low energy and with sub-micrometre spatial resolution,” explains team member Koen Janssens of the University of Antwerp.

The team compared their results to those obtained on artificially-aged oil paint mock-ups that had a similar composition to the lake material. They prepared the latter using an early 20th century cadmium yellow pigment powder and a cadmium yellow oil paint (labelled as Jaune de cadmium citron) that once belonged to Munch himself. They also obtained another set of oil paint mock-ups by mixing powders of cadmium sulphide with equal amounts of sodium sulphate and cadmium chloride, explains study lead author Letizia Monico of the CNR.

To artificially age the samples, the researchers exposed them first to UVA-visible light and a relative humidity (RH) of 45% and then a RH of more than 95% at 40°C for up to 100 days in the absence of light. “The goal of these experiments was to extrapolate the causes that can lead to deterioration,” Monico says.

Moisture is the culprit

The results of these experiments, which are detailed in Science Advances, reveal that the original CdS transforms into cadmium sulphate (CaSO4) in the presence of chloride-containing compounds in high moisture conditions (a RH of 95% and above). This occurs even in the absence of light. The results also show that exposure to moisture causes (Cd,Cl) species to migrate through the paint along with the oxidation of the original CdS to CdSO4. This phenomenon does not occur on Cl-free oil paint mock-ups aged under similar conditions.

Hidden pictures

To mitigate further degradation of the cadmium yellow pigment in The Scream (ca. 1910), Monico says the painting shouldn’t be exposed to moisture levels higher than 45% RH, while lighting conditions should be kept at “normal values for lightfast painting materials”. Currently, the Munch Museum stores and exhibits paintings at a RH of about 50% and a temperature of around 20°C.

Since Munch’s contemporaries, including Henri Matisse and Vincent van Gogh, also used cadmium-sulphide-based yellows, the findings could aid the development of preservation strategies for works by these artists too, explains MOLAB coordinator Costanza Miliani.

“This kind of work shows that art and science are intrinsically linked and that science can help preserve pieces of art so that the world can continue admiring them for years to come,” she states.