Every company wants to attract investors and deter competitors. Patent attorney David Robinson explains how a good intellectual property strategy has helped biomedical physics firm Bioxydyn do just that

A common view of patents is that they are only useful if someone tries to copy your research and product. At that point, so the thinking goes, you need to spend copious amounts of money to enforce your patent and stop them. However, in biomedical physics, as in other fields, patents are not merely a last line of defence against unscrupulous competitors. They are also a deterrent. A timely and well-constructed patent can head off competition right from the start, as it is common (and advisable) for companies to check patent records before launching a product to see if they will be free to market it without infringing other parties’ intellectual-property rights.

An even less well-understood role of patents, though, is as an attractor to investors. Deterring competitors is part of this: because patent protection prevents some would-be competitors from entering a market, it is more likely that one company (and, of course, that company’s savvy investors) will reap any future profits associated with the invention. However, before they can obtain patent protection, applicants must demonstrate that a technology is innovative. This fact is also attractive for investors because it helps to demonstrate the potential value associated with an investment.

Early investor support is particularly important in areas like biomedical engineering, where inventions usually require significant investment to move from the proof-of-concept phase via prototypes to viable commercial products. In addition, innovations in biomedicine demand close attention to regulatory standards designed to ensure safe and standardized product development for clinical applications. Developing new products under these conditions brings its own costs.

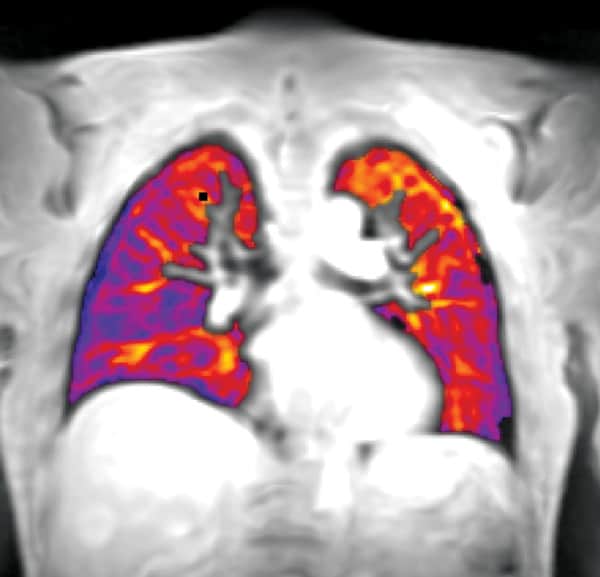

Bioxydyn, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) applications and imaging services provider, is a good example of how patents proved key to attracting investment. Founded in 2009 as a spin-out from the University of Manchester, UK, Bioxydyn uses advanced MRI technology to evaluate lung diseases, including cystic fibrosis, asthma and cancer. Although there had been plenty of academic research into the technology in the years before Bioxydyn was founded, further research identified a way to transform this technology into a clinically practical tool by, among other things, applying novel biophysical models of lung ventilation (the capacity of the lung to receive gas) and perfusion (the blood supply to the lung at the capillary level) to the information available in the images. This made it possible for those viewing the images to draw conclusions about lung health.

Once the Bioxydyn researchers had developed a technique that could prove commercially viable, Manchester’s technology-transfer office encouraged them to consider the patenting process as a means of bringing their technology to market. Following seed investment from a venture-capital fund, the company secured its first service contract with a major international pharmaceutical company in 2011 and has been growing steadily ever since. It is now on the path to acquiring European regulatory approval marking for its technology and launching its first clinical product.

Protecting the right things

When looking to secure intellectual property (IP) protection, one of the first things companies need to decide (most commonly in collaboration with an external patent attorney) is exactly what to protect. Because the protection needs to provide a roadblock to competitors wanting to take unfair advantage of the work, the most common strategy is to protect the technology underlying the main product itself. However, there are strict criteria that need to be met for an invention to be considered patentable, and there are several exclusions. It is commonly believed, for example, that software cannot be patented. However, methods implemented by software can be, as long as they have “technical effect” (that is, a real-world outcome).

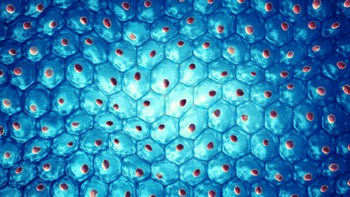

In Bioxydyn’s case, the tools being developed for clinical use are based on software that the company has produced, which is designed to analyse magnetic-resonance images. The tools are also based on the team’s knowledge about the best ways to deploy and implement this software. The company’s patents cover methods embedded in this software that are primarily designed to interpret information arising from a technique known as oxygen-enhanced MRI. With complex analysis so key to physics-based engineering, patents like these – on processing methods implemented by software – will likely become more important to businesses wanting to maintain their competitive edge.

As companies grow, their product developers continue to hone existing products or diversify into new ones. To maintain a deterrent against copycat competitors and remain attractive to investors, savvy companies need to develop their patent portfolio alongside their product range. Although each new patent family requires additional expenditure, robust, well-thought-out protection can help defend or grow market share.

Since obtaining initial protection for its core oxygen-enhanced MRI technology, Bioxydyn has gone on to patent multiple developments within this area. A new version of the core technology that produces richer and more specific information is one example. Another, later example involved patenting different applications for the technology. The initial product focused on analysing oxygen transfer in the lungs alone, but subsequent iterations have gone on to produce imaging techniques that can determine whether an imaged tumour is well oxygenated, while other image-analysis techniques can map the anatomical connectivity between regions of the brain.

A final consideration when seeking patent protection is where to protect. Patents are territorial rights, so for each territory where you want to protect your invention you need a local patent. Budget constraints mean that few organizations file in every jurisdiction globally. Instead, companies look to the most commercially important jurisdictions to prioritize their filings.

Because physics-based products often require sophisticated support technology – Bioxydyn’s services and software, for example, require MRI scanners – most companies in this sector choose to protect their innovations in jurisdictions that include the world’s most developed economies. These are the jurisdictions where potential customers are most likely to have access to the technology required for there to be a market for those services and software. However, as developing economies continue to evolve, so does the need to consider them as jurisdictions in which to seek protection. As more jurisdictions have access to the necessary technology, so new markets open up. In addition, for biomedical applications of physics, the geographic distribution of relevant diseases may also affect the locations where seeking protection makes commercial sense.

Decisions on where to seek protection need to be made fairly early in the patent application process. There are tools to provide more time for decision-making, such as the PCT (international) application, which buys an extra 18 months before a decision on jurisdictions is required. However, after a certain point in time, the decision as to where patent protection will be sought is fixed and you cannot subsequently obtain a patent in a jurisdiction other than those already selected, even if your product suddenly enjoys commercial success there. During the process of obtaining a patent, therefore, decisions will need to be taken based not only on current commercial factors, but also on how markets will evolve in future. Striking a balance between the cost of obtaining protection in different jurisdictions and the potential benefit of having a significant competitive advantage (in the form of a barrier to entry into the market for competitors) is often difficult.

Long-term thinking

The nature of physics research means that often, a great deal of fundamental work must be completed before commercialization appears on the horizon. Even at that point, it can take many more years of engineering, investment and commercial planning to get that research out of the lab and into the real world. While the process for applying for patent protection is also complex and IP strategies need careful forethought and planning, the benefits to R&D-based companies are well-recognized. As different areas of physics research continue to develop and move from the academic sphere to commercial application, intellectual property will continue to develop as an important commercial tool. Start-ups and spin-outs considering their IP strategy from the outset will be the best placed to seize the opportunities afforded by new technologies and retain their commercial incentive for further research and development.