Trailblazing – enjoy the best papers from 350 years of the Royal Society

So what is the site about?

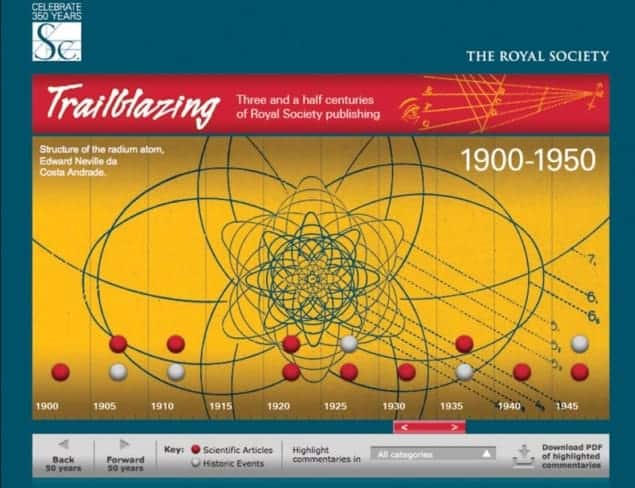

This year marks the 350th anniversary of the founding of the Royal Society, the world’s oldest continuously existing learned society. Since its beginnings in 1660 as a “College for the Promoting of Physico-Mathematical Experimental Learning”, the society has published some 60,000 papers in disciplines from physics to biology, spread over a handful of different journals. Trailblazing brings the daunting scale of this archive down to size with an interactive timeline of 60 papers, carefully selected to reflect the society’s history. Written by luminaries such as Newton, Faraday and Dirac along with lesser-known scientists, all of the papers are available to download free of charge, and each one is prefaced by comments from current scientific experts.

Can you tell me about some of the papers?

Readers will find a little bit of everything in this timeline, which begins with some rather cringe-worthy medical experiments from the late 1660s and continues through to a 2008 entry on geoengineering. Most of the papers are in English, although Alessandro Volta’s 1800 description of the construction of an electric battery is written in French. Among the other physics and astronomy entries, be sure to check out Newton’s 1671 paper containing his “New Theory about Light and Colors”, the 1752 account of Benjamin Franklin’s famous kite-flying investigations and Egon Orowan’s 1938 explanation of metal fatigue. This last paper covers an industrially important phenomenon first spotted by railway engineers more than a century before Orowan, a Hungarian-born physicist then based at Birmingham University in the UK, succeeded in describing it mathematically. While Orowan’s breakthrough may not be in the same league as, say, Maxwell’s unification of electricity and magnetism, it is nevertheless worthy of inclusion. History, after all, is made by good scientists as well as great ones.

What are some other highlights?

The earliest years of the timeline are an antiquarian’s dream, complete with archaic spellings and those elongated letter s’s that look like f’s. It is, however, amusing to see how little some other things have changed since then. In Edmund Halley’s report on the lunar eclipse of 1715, he notes with regret that “my worthy Colleague Dr. John Keill by rea∫on of Clouds ∫aw nothing di∫tinctly at Oxford but the End”. Intriguingly, it seems that Keill’s Cambridge counterpart Roger Cotes had other things on his mind that night – Halley delicately suggests that Cotes “had the misfortune to be oppre∫t by too much Company, ∫o that, though the Heavens were very favourable, yet he mi∫s’d both the time of the Beginning of the Eclip∫e and that of total Darkne∫s”. (Ah, those naughty academics!) Reading such delights online is not quite the same as reading them in the original manuscripts. However, the Web versions are a lot easier to find, and there is even a link where you can sign up to receive free e-mail alerts when new articles cite the timeline articles – although in Halley’s case, this seems unlikely.

What can I learn from the timeline as a whole?

One of the most striking trends that emerges when you look at papers from different eras is the gradual professionalization of science. In the early years of the Royal Society, for example, astronomical observations were mostly being performed by amateurs. By the time Norman Lockyer reported his 1898 discovery that the Sun’s corona is much hotter than its surface, the Reverend Whoevers and Lord Thingummies cited in Halley’s time were almost entirely replaced by Professor So-and-sos. The level of technical detail also increases dramatically. Funny letter s’s notwithstanding, any literate person could read Franklin or Faraday and understand exactly what these pioneers were doing – not least because technical diagrams were, it seems, rather more clearly labelled in the 18th and 19th centuries. Tellingly, the most recent pure-physics paper selected for inclusion in the timeline is Stephen Hawking and Roger Penrose’s 40-year-old work on black holes, but there is still hope for the future: the timeline stretches as far as 2050, and there is plenty of space for new entries.