The March 2015 issue of Physics World magazine, a special issue about light in our lives that is now out in print, online and via our apps, contains a fascinating feature about an astonishing – and largely unknown – superpower that you perhaps don’t realize you have. It might sound bizarre, but using your naked eyes – and with no additional gadgets whatsoever – you can detect whether or not light is “polarized”. And in the video above, Louise Mayor, features editor of Physics World, tells you how.

Obviously you need some polarized light to look at – and one option is to look at ordinary, unpolarized light while wearing, say, a pair of polarizing sunglasses. Another option is to use a liquid-crystal display (LCD) computer screen. As Louise explains above, your best bet is to set the screen to plain white or blue – in fact, in the video we’ve included a few seconds of plain white screen. So if you click on “full screen” and pause the video at that point, you’ll have an instant source of monochrome, polarized light.

All you then need to do is to stare at the polarized light. It might take a bit of practice, but you should eventually become aware of an image at the very centre of your vision. It’ll look a bit like a small yellow bow tie crossed with a blue bow tie and is known as “Haidinger’s brush”, after the Austrian scientist Wilhelm Haidinger who first reported it in 1844. The blue bow tie is aligned with the electric field of the light you are observing, and so you can use this to work out which axis the light is polarized along.

Seeing Haidinger’s brush takes a bit of practice – if you’re looking at an LCD display, you can check if you’re doing things properly by tilting your head slowly from side to side and the brush shouldn’t change orientation. You can find out more about this weird effect in the feature article, which is written by David Shane from Lansing Community College in Michigan. It’s worth persevering, Shane says, because if you can see the brush, then you can look for polarized light anywhere. “Don’t give up if you can’t see it at first!” he insists.

Note that Haidinger’s brush is an “entoptic” phenomenon, which means that the image is created in the eyeball itself, so you’ll never see a photograph of it. As for what causes Haidinger’s brush…well that’s still a mystery.

If you’re a member of the Institute of Physics (IOP), you can now enjoy immediate access to the new special issue about light in our lives with the digital edition of the magazine on your desktop via MyIOP.org or on any iOS or Android smartphone or tablet via the Physics World app, available from the App Store and Google Play. If you’re not yet in the IOP, you can join as an IOPimember for just £15, €20 or $25 a year to get full digital access to Physics World.

For the record, here’s a rundown of what else is in the issue, which is a celebration of light in this, the International Year of Light.

• BICEP2 withdraws cosmic claims – Scientists working on the BICEP2 telescope have backtracked on claims that they had discovered the first evidence for cosmic inflation, as Tushna Commissariat reports

• The mystery of the disappearing physicist – Did the physicist Ettore Majorana not commit suicide, as is widely believed, but go on to live a secret life in South America? Edwin Cartlidge weighs up new evidence

• Leading light – UN secretary-general Ban Ki-moon outlines the importance of the International Year of Light, while physicists reveal what the year means to them

• Meet the kaleidoholics – Two centuries after the kaleidoscope was invented, Robert P Crease stumbles into an incredible world as he visits a physicist who collects these and other “philosophical toys”

• Lighting up the world – More than a billion people across the globe still do not have access to electric lighting. Jon Cartwright talks to those who are turning to light-emitting diodes to supply this most basic feature of modern life

• Night skies get the blues – Light-emitting diodes generate light both cheaply and efficiently, yet by giving off lots of blue light they could worsen light pollution and hamper the quest for dark skies. Gabriel Popkin reports

• The laws of light – Martin Hendry looks at the significance of Maxwell’s equations to our understanding of light

• Unveiling your secret superpower – If you thought weird visual abilities belonged to the realm of the few, think again. David Shane describes a bizarre talent that most sighted human beings have but probably don’t know about

• Rooms with a view – Sidney Perkowitz explains how the camera obscura (“dark room”) and camera lucida (“luminous room”) are still relevant today in science and art, despite the availability of much more modern cameras

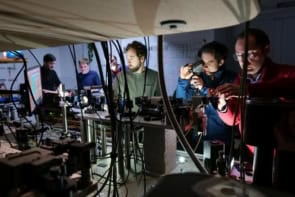

• More than meets the eye – New camera technologies are pushing the boundaries of imaging far beyond what the eye can perceive. Matthew Edgar, Miles Padgett, Daniele Faccio and Jonathan Leach explain how three of these novel cameras work and outline some future applications

• A man, a plan, a bomb – Margaret Harris reviews the play Oppenheimer at the Royal Shakespeare Company’s Swan Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon

• A multiverse play divides opinion – Robert P Crease reviews the play Constellations at the Samuel J Friedman Theatre in New York

• Your career questions answered – Not sure what to do after you graduate? Join the club. Margaret Harris explores the findings of a recent survey that asked physics students to share their career concerns and aspirations

• Acronyms Anonymous – Rick Trebino looks at some amusing acronyms from his physics career