“The thing that becomes overwhelming is that we are used to considering cancer care as one of the highest priorities of the healthcare system. To be in a position where we have to fight for every single aspect of cancer care is a very new position for all of us. It’s like all of a sudden, the diagnosis and treatment of cancer doesn’t matter anymore.”

Shalom Kalnicki, chairman of the radiation oncology department at Montefiore Medical Center in New York, highlighted the challenges faced by radiation oncologists, physicians and medical physicists looking to treat cancer patients in the time of COVID-19.

Kalnicki was one of a panel of experts speaking in a webinar hosted by the Radiosurgery Society last week. The webinar focused on how radiation treatments have had to adapt to the current pandemic. In particular, the participants considered stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS), which delivers precise radiation doses to brain tumours in up to five fractions, and stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT), a similar approach used for extracranial targets.

Hopefully, this will encourage additional studies and investigations into SBRT management of cancer patients

John Kresl, webinar co-chair

One specific concern of any radiation treatment is that it is delivered in a series of fractions over several days, requiring patients to attend repeat hospitals visits and increasing the associated risks. Kalnicki emphasized that each visit must be treated as the first, with patients screened for potential symptoms of COVID-19. He noted that screening patients and staff can add up to 50% extra time to each visit. “Everything takes much longer, nothing is simple,” he said.

So how does this new scenario impact patient scheduling? Helen Shih from Massachusetts General Hospital explained that it’s important to assess which patients really need to be seen in person for evaluation, adding that 90–95% can be assessed via telephone or video consultations. It’s also possible to delay in-person visits for patients with benign diagnoses or non-urgent surveillance cases.

“Cancer is a high priority disease, and anyone who is having active treatment, post-treatment symptoms or concerns for residual disease are still prioritized and seen, remotely or in person as needed,” Shih added.

If patients must attend the hospital, steps are taken for their protection. Kalnicki said that all patients are given surgical masks and gloves when they arrive and are screened for symptoms. At MGH, meanwhile, Shih noted that patients are phoned and asked about any symptoms before each visit.

In some cases, however, rules may be too strict. Michael Schulder, director of the Brain Tumor Center at Northwell Health, NY, described how one fairly disabled patient whom he treated was not allowed to be accompanied by her husband. “I think this is taking restriction to an extreme, common sense has to apply as well,” he said.

It’s equally essential to protect the healthcare workers. Iris Gibbs, at Stanford University Medical Center, CA, explained that the centre has separate entrances for staff and patients, with screening in place at both, as well as a screening app for workers to declare their health each day. But the most important factor in protecting healthcare workers and patients, she emphasized, is testing.

Gibbs explained that Stanford Medicine developed its own test for COVID-19, which was FDA-approved by the end of February. “On March 3, we launched widespread testing within our healthcare community and we’ve been collecting data since,” she said. “When quick 15-minute tests became available, our radiation oncology department had access to that; now all our patients are tested at the time of simulation.”

The situation in New York is less favourable. “As opposed to Stanford, who were fortunate to have their own kits, for now, we are dependent on kits available from industry,” said Schulder. “We only test patients who have a particular set of symptoms, have been exposed to someone known to be infected or are having trans-nasal or sinus surgery. We’re certainly not testing everybody, so that adds a measure of risk.”

Gibbs noted that all treatment planning and dosimetry is performed remotely at Stanford, and for treatment delivery, there’s an emphasis on physical distancing. For SRS, for example, the CyberKnife system has a mode in which the physician can view the treatment console from a different room. For SBRT cases delivered on a linac, however, the physician still needs to be close to the machine.

Site specific changes

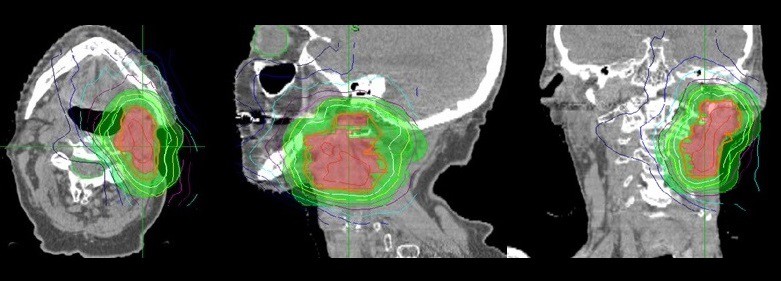

The panel also considered how radiation treatments of specific disease sites are being adapted, starting with tumours of the central nervous system (CNS) and brain. Simon Lo from the University of Washington explained that for high-grade gliomas with poor prognosis and elderly patients, they are using more hypofractionation – in which larger dose-per-fraction is delivered over fewer treatments. At the other end of the scale, patients with low-grade gliomas will have their treatment delayed where possible.

“For post-operative SRS of surgical cavities, I usually favour treatments of 3–5 fractions,” said Lo. “But a lot of our patients come from surrounding states, so to minimize visits, I would do a single fraction treatment instead, knowing that the BED [biologically effective dose] may be lower. But we need to strike a balance between virus exposure versus BED delivered to the cavity.”

At Northwell Health, said Schulder, all benign SRS has been deferred. Patients with malignant tumours are still being treated, but with 3-week rather than 6-week fractionated radiation. He also noted that all non-COVID-19 clinical trials have been shut down.

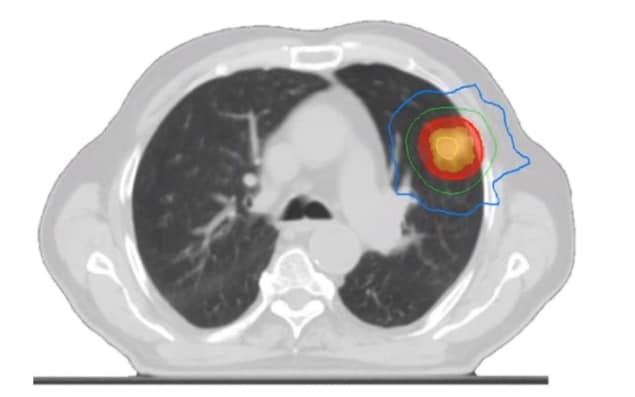

Shankar Siva, who leads the SABR programme at the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre in Australia, explained that lung cancer treatments have also changed dramatically. The centre has switched all patients with peripheral early-stage primary lung cancer to receive a single fraction of 30 Gy. “There are three randomized phase 2 studies in lung that give us some confidence that moving to single fraction schedules is the way to go,” he said, adding that fractionated SBRT is still used for centrally located lung tumours.

Jun Yang, chief medical physicist at Philadelphia CyberKnife, noted that his practice is hesitant to move to single-fraction treatments. “Even in this critical time, we pretty much still stick to 3–5 fractions,” he said. “For a lung cancer patient, we actually would stick to the SBRT plan as much as we can to speed up the treatment and lower the patient’s chance of getting the virus.”

Patients with prostate cancer face another hurdle. Radiotherapy of such tumours usually requires implantation of fiducial markers to ensure accurate targeting. But in New York, said Kalnicki, state law precludes the placement of fiducial markers as it is considered an elective procedure, which is not allowed.

Najeeb Mohideen from Northwest Community Hospital, IL, is still performing fiducial placements for prostate cancer radiotherapy, but only under local anaesthetic, which does not require anaesthesiology services. Indrin Chetty, a medical physicist at Henry Ford Health System, MI, pointed out that cone-beam CT could provide an alternative, even in the SBRT setting, if slightly larger margins and lower fractionations are used.

What does the future hold?

Finally, the panel considered whether the approaches currently in place will impact radiation treatments in the future. Gibbs suggested that we are “forever changed”, and that risk mitigation and protection measures will continue. Hypofractionated treatment could also remain. Some centres have introduced hypofractionation for the first time, and if similar clinical outcomes are seen, may adopt this in the long term, she explained.

Siva agreed that some habits are likely to stick, such as electronic rather than paper consenting. He thinks that the Peter Maccallum Cancer Centre may continue to use a single radiation fraction for treating primary lung cancer, but that this decision will be centre-dependent.

John Kresl, from the Phoenix CyberKnife and Banner Good Samaritan Medical Center, AZ, pointed out that several surgeons have contacted him to ask about non-surgical options for their patients at this time. “I’ve had referring physicians call that maybe weren’t aware of, or were resistant to, SBRT and were asking questions about having patients treated. Hopefully, this will also encourage additional studies and investigations into SBRT management of cancer patients,” said Kresl, who co-chaired the webinar with Ben Slotman from Amsterdam UMC in the Netherlands.

“Amidst all the destruction the virus will leave in its wake, inevitably there will be opportunities to do things better,” concluded Schulder. “There are things that we’ve already adjusted to and should keep going – related to patient selection, treatment planning and delivery. I’m sure we’ll be able to make some good out of all this.”