David Appell reviews The Little Book of Cosmology by Lyman Page

In the latter half of the 20th century physicists undertook a shrewd move: they began to take the entire universe as their laboratory. It was a clever manoeuvre based on real-estate values alone, but it had other advantages as well. Floor space was essentially unlimited, maintenance fees were negligible, it cost nothing to heat and cool, and no insurance policies were required. But getting through the door, or even watching through a window, was costly. Of course, astronomers and physicists have always used observations of the universe to hone their understanding of the world.

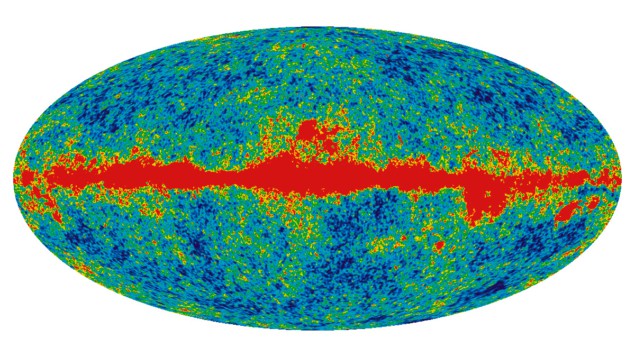

As Lyman Page – the eminent Princeton University cosmologist – recounts in The Little Book of Cosmology, it was the discovery of the cosmic microwave background (CMB) that started the age of cosmology we’re in now, something that hadn’t much interested astronomers until then.

“We cosmologists,” writes Page, who studies temperature variations in the CMB, near the end of this clearly written, delectable book, “feel fortunate to have been alive in the decades when the explosion of knowledge about the universe took place.” He has made good use of these feelings to produce this enthusiastic and approachable survey of the state of cosmology today. This is hardly a surprise, as Page is an expert in observational cosmology, being one of the original co-investigators of the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) project, and has won numerous awards including the 2018 Breakthrough Prize in Fundamental Physics, the 2015 Gruber Prize and the 2010 Shaw Prize.

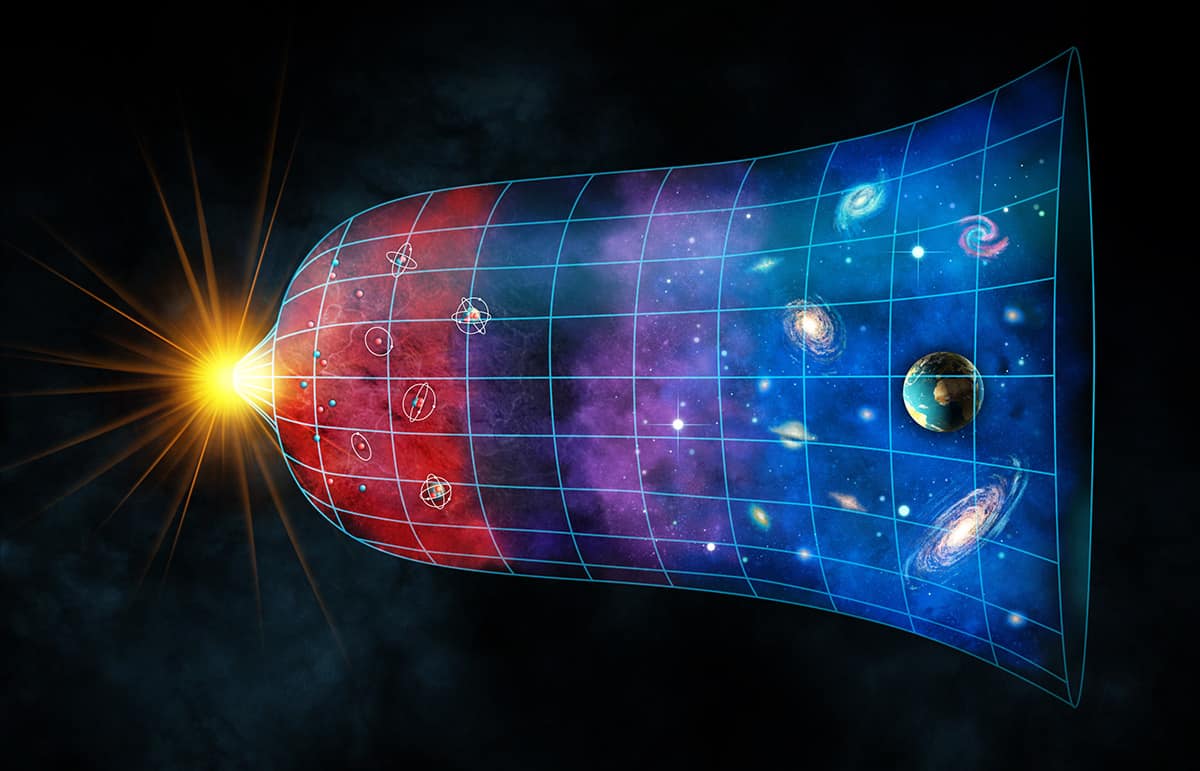

In The Little Book of Cosmology, Page uncovers the discoveries that have led to some of the most interesting and astonishing phenomena in all of the sciences. The book touches upon the cosmological constant of empty space; the accelerating expansion of the universe; the fact that ordinary matter makes up only 1/20th of the energy density of the universe; the mysteries of dark matter and dark energy; the slight (about one part in 100,000) but exceedingly informative temperature variations of the CMB as seen across the entire sky. In truth, at 185 pages this book is more than a survey, but still something you can read without a pen in your hand and a tablet before you. The book includes forays into more advanced topics as well, though not to the same degree. Page introduces inflationary models of the very early universe, how the gravitational landscape of the early universe produces anisotropy of the CMB, gravitational lensing of the CMB, and quantum fluctuations as a basis for cosmic structure.

A heartening feature of the book is Page’s repeated emphasis on precise measurement as the best way to test ideas, theories and models. He gives examples of where this has already been done, perhaps most spectacularly with the determination of the power spectrum of the CMB as measured by the WMAP and Planck satellites. That a relatively simple cosmological model, with just six free parameters (beyond those of the Standard Model of elementary particle physics), explains this non-trivial, shapely curve is a true masterpiece of scientific achievement.

The book ends with a chapter on the frontiers of cosmology, what remains to be known, and what might be known soon. Sensitive upcoming galactic surveys will see the effects of neutrinos on cosmic structure, and perhaps give more precious information about their masses, for which only limits exist today. Primordial gravitational waves may reveal secrets about the infinitesimal era of quantum gravity. Galactic and CMB surveys could reveal small deviations in the expansion rate versus time, and hence changes from predictions of an unchanging cosmological constant. Meanwhile, instruments are being designed to look for CMB radiation departures from a blackbody spectrum.

Planck perspectives

In many ways The Little Book of Cosmology reminds me, in mission and style, of Steven Weinberg’s 1977 book The First Three Minutes, which sits on my desk as I write, its matured pages smelling a bit like soap, its lower right-hand corner having been nibbled on by a mouse. Weinberg includes more numbers, but no plots. Page’s book has an exceptionally clear and direct style of writing. There are no equations in this book except for the famous little one of that Einstein fellow (which is more for show), some graphs and only a few spots that require multiplication. It avoids scientific notation until an appendix, to my chagrin as I struggled with the written number “one ten-millionth.” Surely anyone who can understand the bulk of this book can understand scientific notation from the get-go. Also, I was somewhat surprised to find Alice and Bob gallivanting across the universe, explaining inflation and other concepts – indeed, it was a bit disorienting.

I don’t think the revelations and the remaining mysteries presented in this book have yet penetrated much of the public, which is a lowdown shame

I don’t think the revelations and the remaining mysteries presented in this book have yet penetrated much of the public, which is a lowdown shame. After all, how much we have learned about the cosmos over the last 20–30 years, how precise the measurements have become, how tightly constrained the most successful model is. But yet, we still don’t know what 95% of the universe is made of. There’s something untoward about saying space is being created everywhere, and there are portions of universe constantly fading from our view. Still, those costly windows into the ultimate laboratory are providing ever clearer views. It is no place for the timorous.

I think this book can open the eyes of many motivated readers – smart high school students, university students regardless of their course of study but particularly those assigned it in an introductory astronomy class, members of astronomy clubs, physics students looking for a quick introduction to the field, and certainly anyone who reads this or any other science magazine. It’s got to be the best, most up-to-date, “little” introduction to cosmology they’re going to find.

- 2020 Princeton University Press 152pp £16.99hb