Whether it’s at a concert, play or lecture, we love to show our appreciation by clapping our hands. Laura Hiscott hears from two researchers who know how to make great applause

It might be hard to imagine yourself in ancient Rome, but if you were dropped into the audience of a play 2000 years ago, you’d probably know what to do when it finished – start clapping. Making a sound by putting your hands together is in fact such a long-standing practice that no-one knows quite when or how it started. Clapping certainly seems to have been well established when the Romans were around.

Some people have even made a profession of it, notably the “claqueurs” of 19th-century France, who received money and free tickets in return for particularly zealous applause. But I wonder if any of these entrepreneurs ever considered the physics of their trade. Imagine if they tested various clapping techniques to find out which would please their client most. After all, there’s more than one way to crash two hands into each other, so which is best?

The loudest configuration is one in which the hands are held at about 45 degrees to one another and the palms partially overlap

It’s a question that inspired Nikolaos Papadakis and Georgios Stavroulakis – two engineers at the Technical University of Crete – to investigate. While teaching acoustics, Papadakis found that his students often wanted to know how they could measure sound without using any expensive equipment. For acoustic measurements like these, you generally need a short but loud sound source – and there’s nothing cheaper than a handclap.

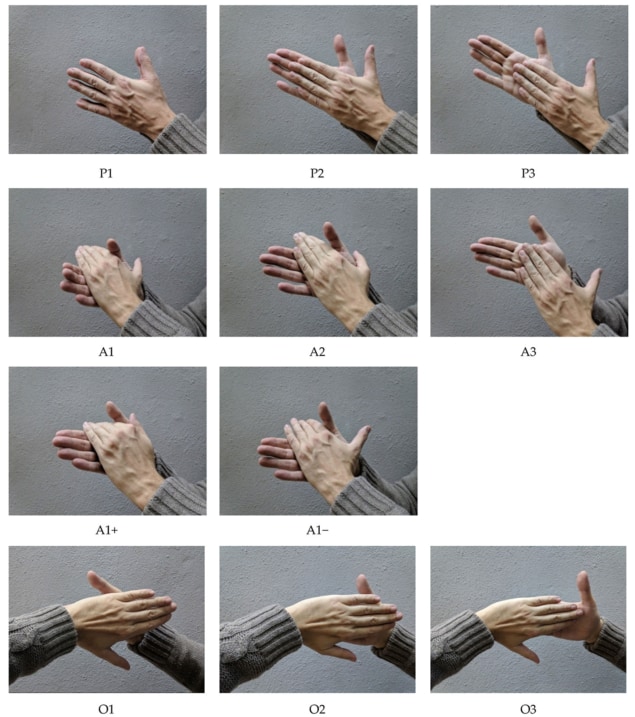

To see how well handclap measurements fared against those made with expensive acoustic kit, the researchers got a group of 24 students to perform single handclaps at various venues in no fewer than 11 different hand configurations. Each of these was defined by a unique combination of the angle at which the hands are held to one another and how much the fingers of one hand overlap with the fingers or palm of the other.

Although it might be a bit late to help the claqueurs, the results are in (Acoustics 2 224). The loudest configuration, generating an average sound pressure of 85.2 dB, is one in which the hands are held at about 45 degrees to one another and the palms partially overlap (A2 in the figure “Hear, hear”).

But decibels aren’t everything when it comes to sound: the frequency distribution is vital too. So what works best there? Turns out there is one mode of clapping that produces particularly low tones. This involves keeping the hands at 45 degrees, but with the palms fully overlapped and slightly domed to enclose a pocket of air (A1+ in the figure).

While both flat and domed handclaps disturb the air and create pressure waves that our ears detect as sounds, they do so in slightly different ways. As two flat hands collide, the air between them is forced out increasingly quickly, ultimately exceeding the speed of sound. This creates an abrupt pressure change, resulting in shock waves that make up a large part of the noise we hear.

With cupped palms, meanwhile, there is usually a gap left around the thumbs, so not all the air is expelled. This makes for slightly gentler pressure changes that do not create much of a shock wave, but which produce what’s known as a Helmholtz resonance.

“In general, a Helmholtz resonator is a container of gas with an open hole,” says Papadakis. “At the Helmholtz resonance, a volume of air in and near the open hole vibrates because of the ‘springiness’ of the air inside. This vibration creates sound at sufficiently low frequencies that other handclap configurations cannot produce at such volume.”

This is the same phenomenon underlying the hum you get from blowing across a bottletop, as well as that uncanny “sound of the sea” in a seashell. In the latter case, environmental fluctuations in sound pressure enter the shell and get reflected off its hard inner surfaces, with resonant frequencies getting amplified in the enclosed pocket of air and simulating the whooshing of ocean waves.

As poetic as it might be to use a seashell, you can actually recreate this effect using just your hands. If you put your domed palms together, leaving a gap where your thumbs overlap, and hold this gap to your ear, you may well hear that familiar hiss. You can even play around with varying how domed your hands are and hear a noticeable change in frequency as you do. When you clap your hands together into this shape, you generate a brief, loud pulse at these resonances.

Shreddinger’s equation: when the uncertainty principle goes up to 12

So, equipped with these insights, has Papadakis changed the way he claps? “Surprisingly, yes!” he says. “Especially at concerts that I have really enjoyed and when I want to express my enthusiasm and appreciation to the artist, I prefer to do the domed handclap with the Helmholtz resonance. This is probably because I can more easily distinguish the sound of my own handclap among the overall sound of clapping, and because the richer frequency content with more volume in the low-frequency range expresses my enthusiasm better.”

As for me, I have found myself trying out the different handclaps while I’ve been writing this article (apologies to my co-workers) and I’ve already noticed myself applauding more consciously at concerts. Who knows? Maybe if I cultivate a suitably conspicuous clap I’ll convince someone to give me free tickets. Taylor Swift, can you hear me?