Graeme Malcolm, co-founder of M Squared, describes how his company started by making robust, narrow-linewidth lasers for the scientific market and is now branching out into new fields and applications

What was your career like before you started M Squared?

I watched the first space shuttle launch when I was at school, and I remember sitting there thinking, “Geez, I don’t know what I want to do in life, but I want to do something like that.” I went on to study laser physics and optoelectronics as an undergraduate at the University of Strathclyde, UK, and my main motivation for choosing that course was that it looked like the industry of the future. It turned out that this was at least partly true, in lots of exciting ways that people might not have imagined back in the late 1980s.

I stayed at Strathclyde to do a PhD in solid-state lasers, and that’s when I met my co-founder and business partner, Gareth Maker. Our first business was a company called Microlase that spun out of Strathclyde in the early 1990s. We made short-pulse lasers for multiphoton excitation spectroscopy and deep-UV lasers for applications in things like optical data storage or semiconductor manufacturing, where you need a very small laser spot.

In 1997 Microlase partnered with Coherent, which was the largest public company in laser technology at the time. Then, in 2000 Coherent acquired our business – it’s now known as Coherent Scotland – and Gareth and I stayed on to grow it as part of a bigger multinational. This was before the telecoms bubble burst, when the optical backbone for the modern Internet was being developed, and there was a lot of innovation going on. The data rates we’ve now come to expect just wouldn’t have happened without that progress in lasers and fibre optics. Being inside a Silicon Valley company was also interesting, and we learned a lot about how they sold and marketed their products across multiple sectors.

By the mid-2000s, though, it was time to do something new. In going from Microlase to Coherent, we’d gone from being a couple of guys in a room with no windows to being a substantial part of a big corporation. I’m not quite sure how to describe it, but someone once told me that in life you get people who are “finders”, coming up with ideas for new things; people who are “grinders”, working out the details to make those new things happen; and people who are “minders”, keeping the process going once it’s started. For us, working at Coherent had become more of a minding than a finding or grinding job. We were doing more of the same things, but we weren’t getting the chance to explore and develop new ones. If I’d wanted to go further in my career at Coherent, I would have needed to relocate to Silicon Valley, and that just wasn’t me. So instead, we established M Squared to develop new ways of using light for good, opening up applications that have strong commercial potential while also addressing problems in areas that are important for society.

How did you decide what to focus on?

When Gareth and I left Coherent, we had a clean sheet of paper. That gave us the chance to step back and ask, “What does this industry need? What’s likely to be important in the future? And how is that different from what’s available now?” One of the answers we came up with was that lasers needed to be more reliable, so that customers could get them into their applications right away. That led us to focus on improving optomechanical stability and developing robust control systems. Those are big challenges, so we decided to tackle them using narrow linewidth lasers – a technology that was already familiar to us – and to start with the scientific research community as our customer base.

Science is like a signpost to the future. Having scientists for customers has given us the direction we need to understand where laser technologies will be important. For example, the first people we sold our lasers to were doing research in what’s now called quantum technologies. At the time, it was known as atomic, molecular and optical physics, and it seemed like a very niche part of the science base, but it’s now an important emerging field that’s making its way into very large commercial markets. So we picked an area that let us build on our core competencies, while also adding a couple of elements that we thought would be important for the company’s future. That’s helped us get the foundations right, so that as our product portfolio has grown, we’ve got the dependability that lets us get into bigger industrial applications.

Can you give me an example of those applications?

Our SolsTiS laser technology was used to calibrate the European Space Agency’s Sentinel-5P Earth observation mission, which has become the best instrument we have for measuring air pollution on a global scale. It’s producing beautiful maps of the way our industrial processes are affecting the health of the planet. We’re also involved in a project to measure carbon dioxide emissions from space, which will make it possible to see where people are producing CO2 and where it’s getting absorbed by forests and oceans.

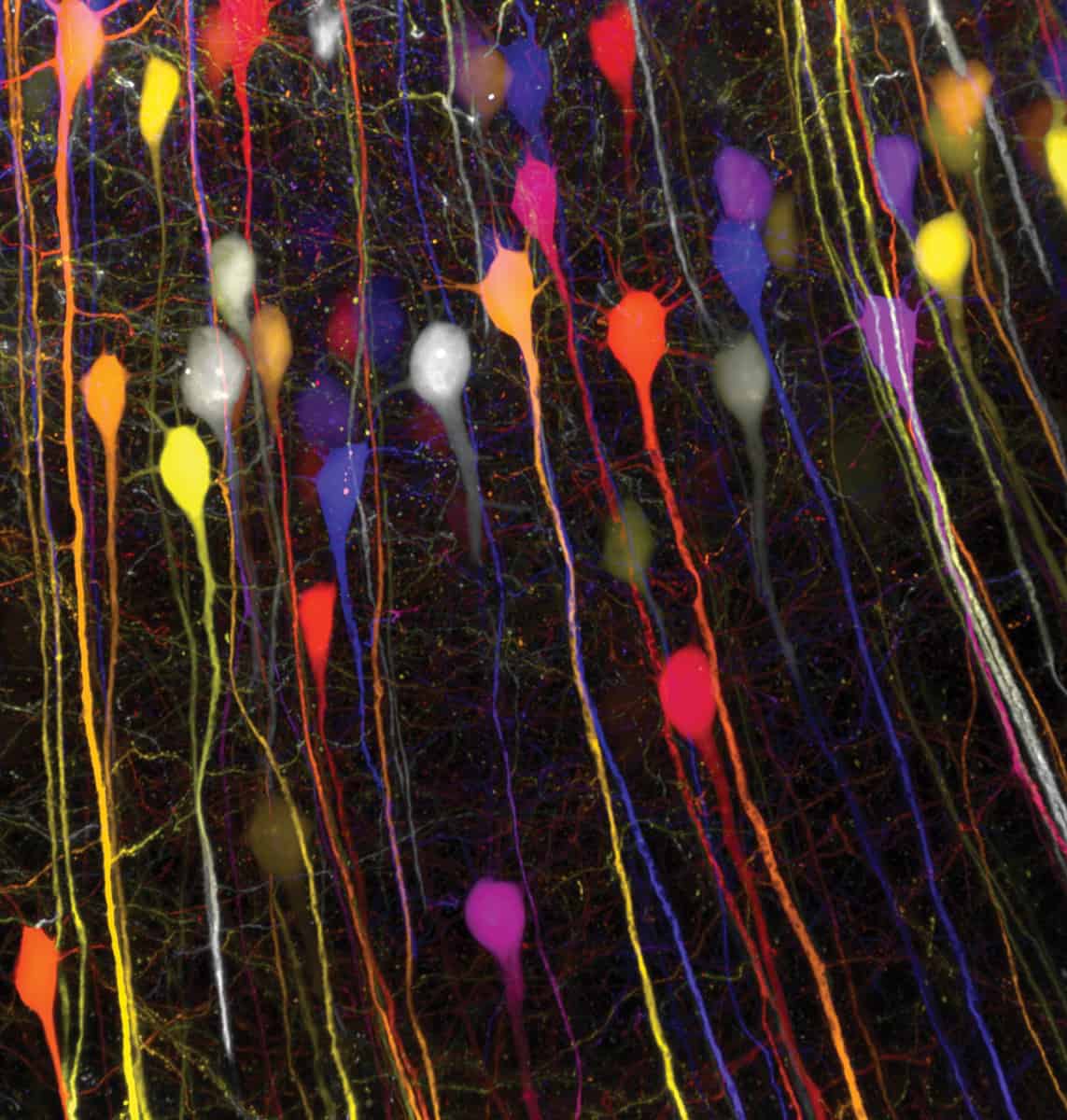

Over the last two or three years, we’ve also worked with researchers at the University of St Andrews here in Scotland to bring a new biological imaging technique known as Airy light sheet microscopy to market. This is a laser and digital imaging system that gives you resolution on the micron scale – small enough to look at the biochemical processes taking place inside cells (see image above) – over a relatively large area, several hundreds of microns on a side. That means scientists can use this microscope to look at large collections of cells and start to understand the processes of life better.

You and Gareth had started a company together before. Did that make it easier to get funding for M Squared?

The first time you start a company, everybody tells you that you need a track record to get funded. The second time around, they tell you it’s not quite as easy as that. But the thing we got right was to step back and ask what we needed funding for, how much we needed, and when. It can be easy to get on a perpetual treadmill of constantly raising funding to grow a business, but it’s a very time-consuming process, and Gareth and I have a very strong belief that you need to look after the fundamentals first.

So we had a period where we decided to keep things lean and invest some of our own money, in order to de-risk our business proposition by working around the core challenges and doing some detailed development. That way, when we were ready to seek funding, we could do so with our best foot forward. We also got strong support from Scottish Enterprise, and at the end of the first year we raised some money from a private-equity house in Edinburgh, Melville Capital. Angus Kennedy Morrison, who heads up Melville, has been a great supporter of our business, and he still sits on our board, so we made a good pick there.

For about five years after that, we took the view that the best people to fund the growth of our business were our customers. If what we were doing was valuable – and if we had a decent business model that created the right margins for the right level of investment – then end users and customers would pay for it. But there are also certain points in the life of a business where you need to raise capital to make step changes that you can’t otherwise make. We reached that point in 2011, when we raised £4m from the Business Growth Fund to develop a scaled-up factory and set up a sales and marketing team in North America, a region that now accounts for more than half of our business.

What was the most difficult part of developing M Squared?

The entrepreneurial journey is all about heading down a path where the scale of your vision and ambition is completely mismatched to your available resources. You’ve got to realize that. You’ve got this gaping chasm between what you’d like to do and what you are functionally able to do, and the challenge in any high-growth entrepreneurial business is to work out how you’re going to close that gap, step by step.

To me, the answer is, predominantly, by getting the best people to help you. In the early years, many of M Squared’s employees were people like ourselves who had been around the block in the laser industry, but we also had people working on electronics and control systems who came from a Glasgow company that made very high-end audio systems. Having that expertise is the essence to closing the capability gap. Today, about a third of M Squared’s staff come from outside the UK, and the importance and beauty of that diversity is that it gives you different insights, different types of creativity and a fundamental ability to do bigger, faster, more challenging things.

Any advice for someone starting a business in optics or photonics?

Don’t try and do it all yourself. Find things that other people can help you with and ask for help as often as you possibly can, because then you’ll move faster and avoid the pitfalls that other people have seen before. But the main thing I’d say is that I’m amazingly optimistic that we’re coming into a golden era of optics and photonics, where the industry is having a more and more positive impact on the world. That’s been a key part of M Squared’s story, but I think it’s becoming even more so as we begin to see the potential for some of these technologies.

- Enjoy the rest of the 2019 Physics World Focus on Optics & Photonics in our digital magazine or via the Physics World app for any iOS or Android smartphone or tablet.